|

|

|

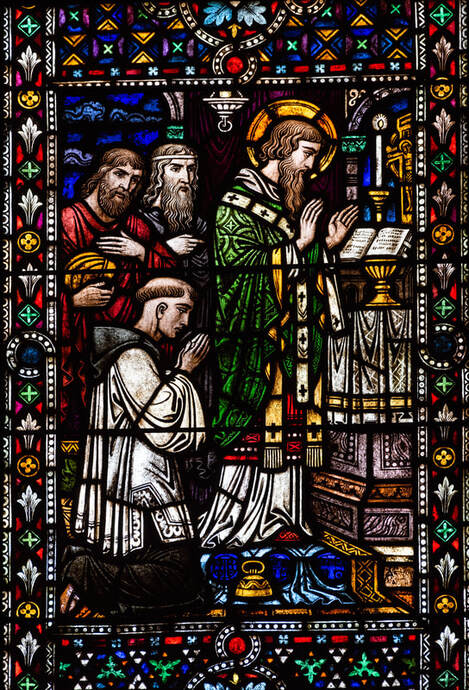

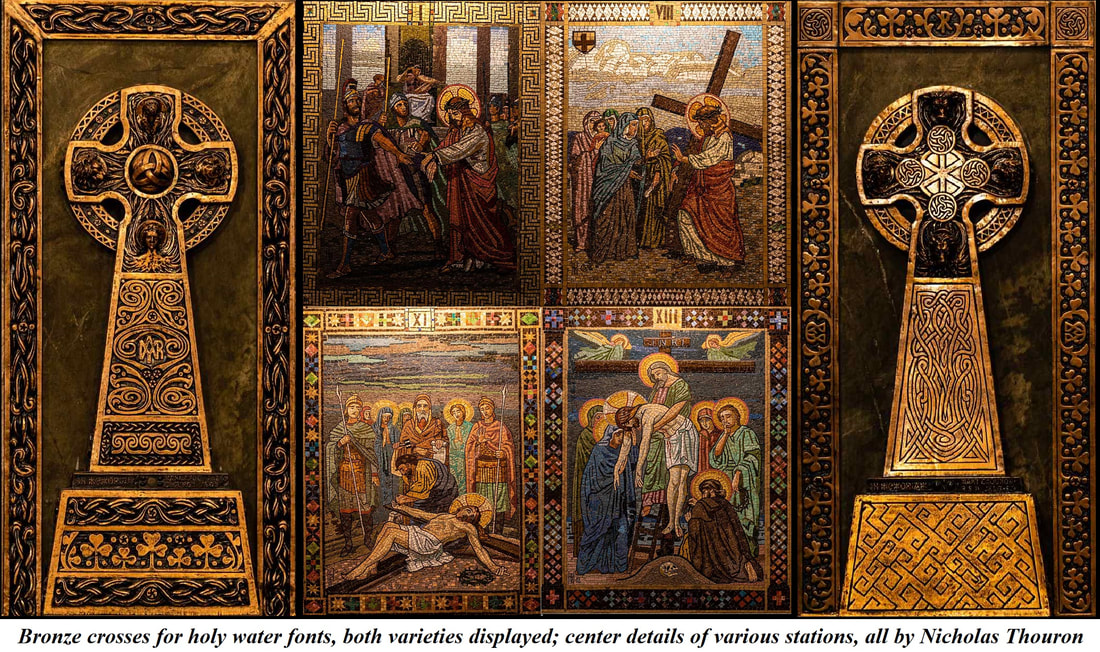

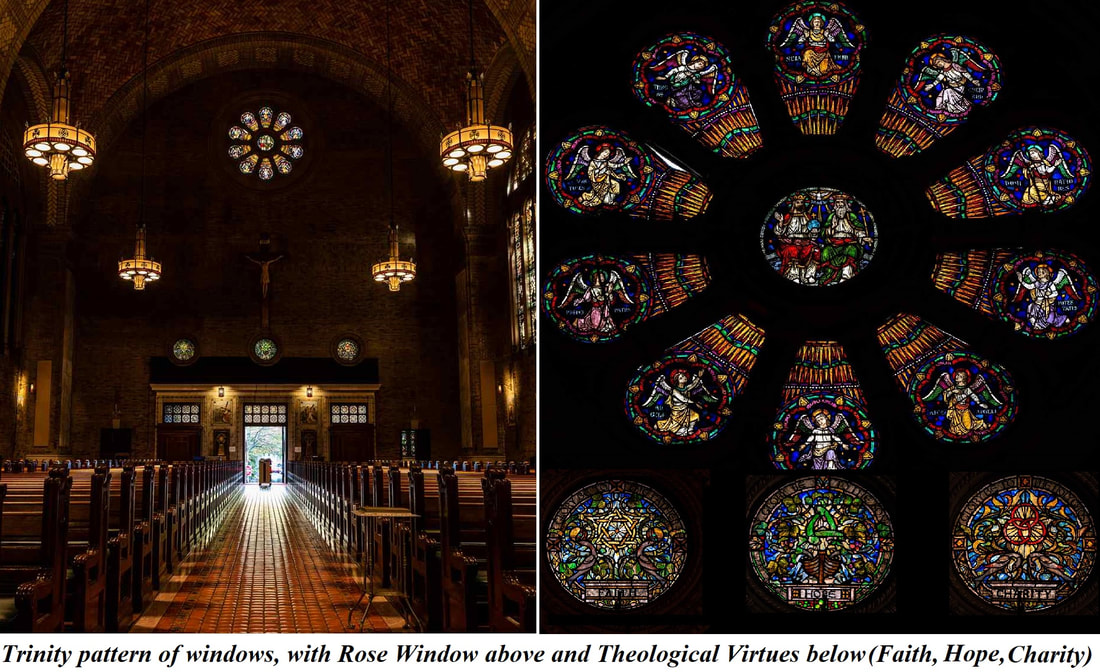

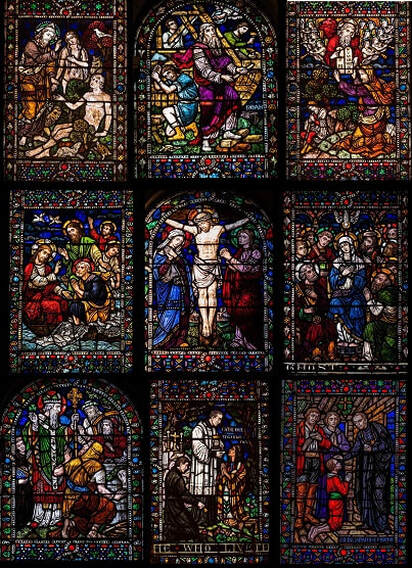

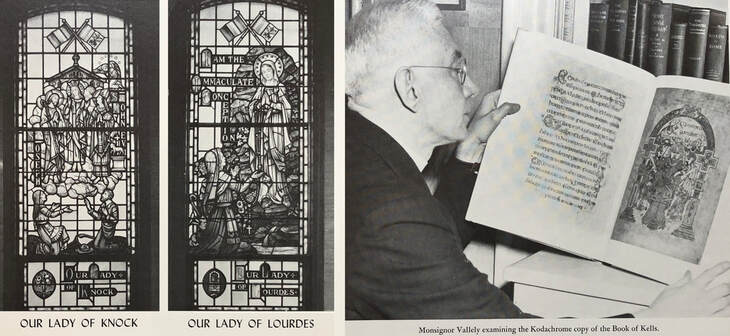

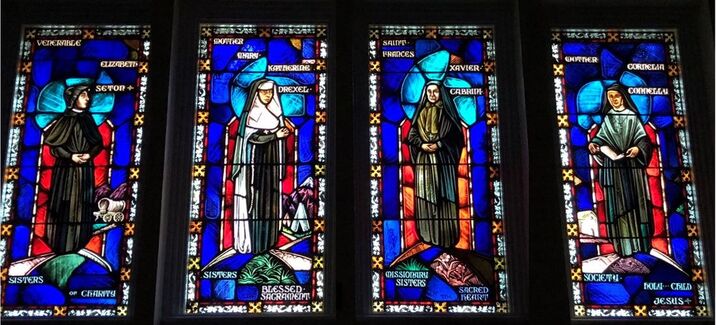

Our Stained Glass Windows

|

To obtain a beautifully printed edition of our beautiful new Rosary booklet featuring stained-glass windows of St. Patrick Church for only $10 a copy, contact our parish office at [email protected] or call (215) 735-9900. You can also purchase a copy online through the link below and come by the office to pick up your order. |

|

Salvation History Windows

Upper Church |

|

Other Windows & Photos

Upper Church |

|

Christ With Me, Christ Before Me

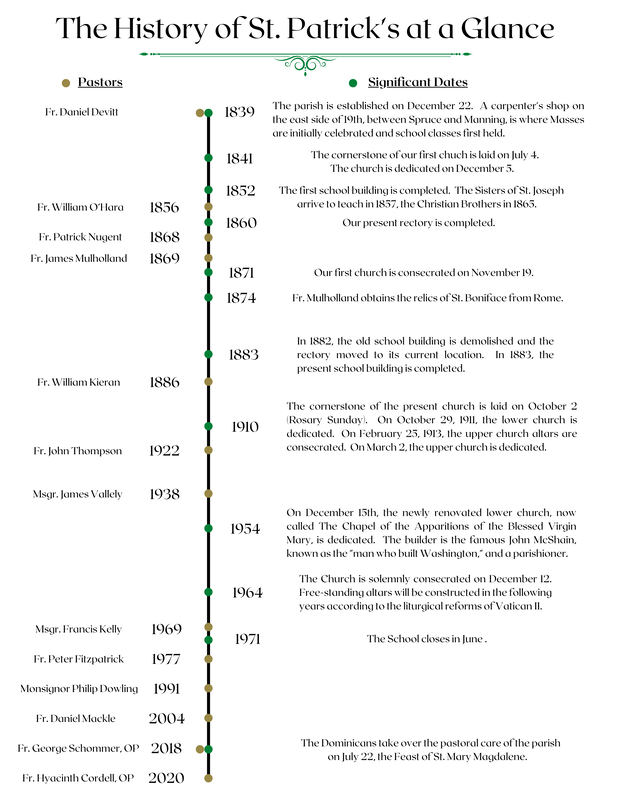

A History of St. Patrick's Church (Founded 1839)

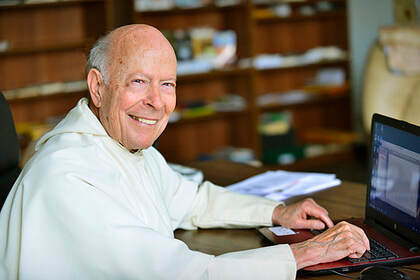

By Timothy Danaher, O.P.

From written and oral traditions

April 2020

____________________

From written and oral traditions

April 2020

____________________

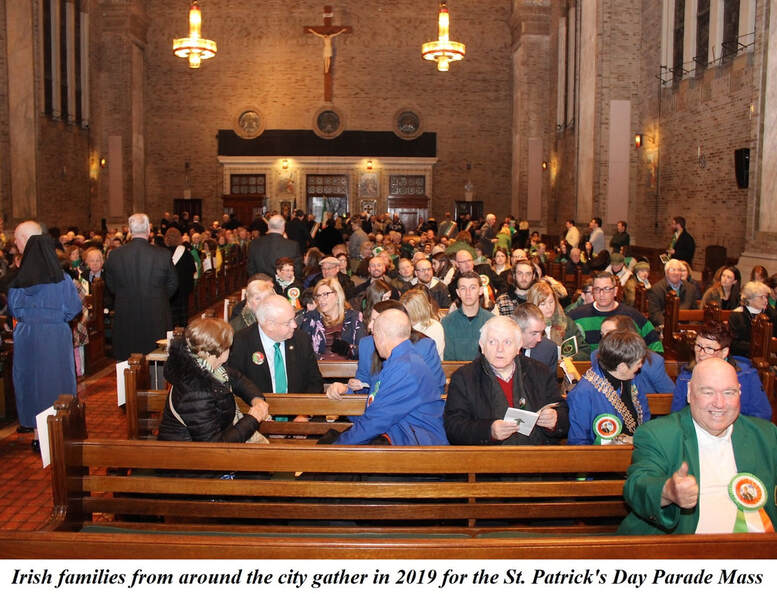

Apology: I write this history for the people in our neighborhood who know it already, those who were born here and told me the stories which until now have lived only in their memories and deserve to be put on paper. I write this history for those in the people in our neighborhood only think of the Spread bagel shop or Ultimo Coffee, who just arrived and who walk past our church doors and all other row home doors and know nothing of the people that came before them. I write this history for myself, as I have recently arrived and recently realized that I live and serve in a place of immense history: local, international, religious, and civic. To look into the past, to open the door just a little, is to discover many things. I write this history because roots matter, and they teach us, as they help us breathe more deeply in an age when we are convinced that everything that happens is new, which is simply not the case. Glory to God. Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever. (April 2020)

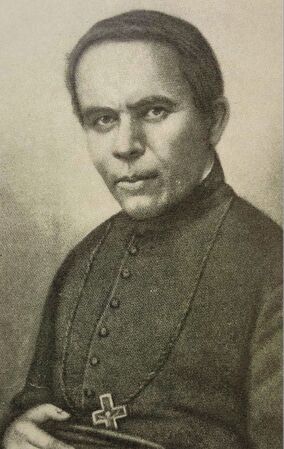

I. Bishop Kenrick and Early Dominicans

Bishop Kenrick, who founded the parish, wrote in his diary on December 22 of that year: "A chapel was opened in Schuylkill Fourth Street near Spruce. Fr. E. Sourin preached, the Fr. Daniel Devitt celebrated Mass... I have rented this house for a time, with the hope that in a short time a church might be built in the vicinity."

|

Kenrick was born in Dublin and had been educated in Rome, arriving there in 1814 during the heroic return of Pius VII from his years of captivity under Napoleon. He completed his studies at the Urbaniana college for missionaries, then was ordained a priest in 1821 and volunteered to serve in America. He taught seminarians Greek and History at St. Joseph's College in Bardstown, Kentucky. (This diocese was created along with Boston, New York, and Philadelphia on the same date, April 8, 1808, all new branches from Baltimore, our nation's first Catholic diocese.)

|

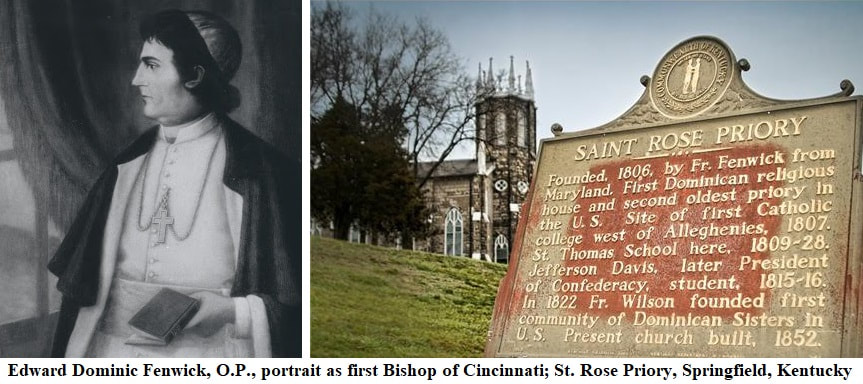

Here begin some surprising and providential ties to the Dominican Friars, who presently have care of St. Patrick's Church. In Kentucky, there were only a handful of priests, except for the Dominicans who lived down the road in Springfield. Here was their headquarters in the United States, founded in 1805 by Edward Dominic Fenwick, O.P., who later was named the first bishop of Cincinnati. He was one of those present to consecrate Kenrick a new bishop for Philadelphia in 1830, which happened in Bardstown before he left to begin work in this city. He had spent 9 years teaching, and after 9 more years as bishop he would found St. Patrick's Church on December 22, which is also the founding date of the Dominicans themselves since 1216. Another hint of providence is found in that the Knights of Columbus would soon purchase a building right next door to our parish (presently the Koresh Dance Company), named the San Domingo Council, the same saint who founded our Order.

The first Dominican priest arrived in Philadelphia in 1808, Fr. William Harold, O.P. of the Irish Province. He arrived to assist his fellow Irish Dominican, Luke Concanen, O.P., appointed the first bishop of New York. He, however, never set foot on American soil. Napoleonic blockades controlled the port in Naples, so from there he administered the diocese by letters to his mission priests, and there he died and was buried at the Church of St. Dominic. Harold was quickly recruited by Philadelphia’s first bishop, Michael Egan, O.F.M., who made him the first vicar general of the diocese and his groomed successor. The two fought, however, and the very outspoken Harold returned overseas in 1813. He would return again from 1820-1828 as collaborator with the second bishop, Henry Conwell, this time with fellow Dominican, John A. Ryan, O.P. Harold even served as pastor of Old St. Joseph’s during the Jesuit suppression!

This continued until the Hogan Schism divided everyone involved. Conwell had walked into a mine field. Since the death of Egan, the young diocese had been 6 years without a bishop. Technically its administrator was a German named Fr. Louis de Barth, who had refused the offer of bishop, lived in New Jersey, and was cold towards the Irish. The diocese carried on with the service of a variety of mission priests, some stray diocesan priests and other Franciscans or Cistercians fleeing Europe’s attacks upon monasteries in that era. (The British Colonies were served by an array of roaming priests, a good example of which is the Trappist, Fr. Jeremiah O’Flynn, who’s political and religious journeying mimicked Gulliver’s Travels, setting off from Ireland, then onto Rome, Australia, Philadelphia, Santo Domingo, and his final years were spen in, you guessed it, Susquehanna County. The first 186 priests to serve in the colonies, however, were all Jesuits, based in Maryland ever since first Mass was celebrated at St. Clement’s Island by Fr. Andrew White, S.J. on March 25, 1634. This changed with their suppression in 1773. The priests at Old St. Joseph’s acquired diocesan status but left for Georgetown in 1799.)

At last, in 1820, Conwell was named, a life-long Irishman who was then 75 years old, the age today at which all bishops must submit to the Holy See their retirement letter. His rival to which he recently lost in vying for the See of Armagh commented on the American news that he wouldn’t be more surprised if he was named as Emperor of China. The brand new geriatric bishop arrived on these shores fairly blind, in poor health, worried over personal finances, and about to face the trustees.

Bishop Carroll had imitated the Episcopalian structure of having parish trustees, but their decisions did not extend to hiring or firing pastors. At St. Mary’s Church, Fr. William Hogan was the most favored, known for insulting other priests in his sermons and also for building his own private residence. When Conwell ordered he return to live at the clergy house, the trustees reacted by firing all priests from the board, electing Hogan their pastor, and banning the bishop from setting foot in his own cathedral. They also wrote a letter to all surrounding Catholics to break away with them and form a new American Church. Hogan was, understandably, stripped of his faculties. Elections for a new pastor the next year resulted in a brawl, which included throwing bricks, finally broken up by the police. Pius VII eventually wrote a letter reprimanding the St. Mary’s trustees, asking for their reorganization.

Tangled up in the affair were other priests who weighed in with opinions. One was Harold’s own uncle, Fr. James Harold, a diocesan priest once shipped off to Botany Bay for conspiracy against Britain and now present and money-grubbing and not helping achieve any peace. Another was a Spanish Franciscan named Friar Rico, who was a canon lawyer, but worked most weekly hours in the city as a cigar salesman. Neither quite helped the cause. In 1826, Conwell signed a truce with the trustees, splitting the difference with them recommending pastors and he approving. It was enough to get him summoned to Rome and removed forever from administration of his diocese. It also separated him from Harold and Ryan. The two Dominicans stayed on to serve in parishes, until Bishop Fenwick of Cincinnati arranged for their Order in Rome to assign them to his diocese. They appealed to Secretary of State Henry Clay that their rights were violated, but when the appeal fell flat, they returned to Ireland again. Harold would become Irish Provincial later in life. The next Dominican arrival to Philadelphia was Fr. John Dominic Berrill, O.P., the founding pastor of St. Dominic Parish in 1849. As a community, Dominicans first arrived at Holy Name of Jesus Church in Fishtown, serving from 1912-1998, as well as teaching at La Salle University and St. Charles Seminary.

Francis Kenrick was the one to pacify the diocese at last. Conwell traveled to Kentucky to ordain him as coadjutor bishop (but also apostolic administrator, i.e. the one who held the keys now). The two sailed north up the Ohio River (past my hometown of Steubenville, Ohio), and they disembarked in Pittsburgh which was then the western edge of the Philadelphia Diocese. By stagecoach, and with many stops to preside over Confirmations and new church dedications, they traveled east across the state towards Philadelphia. The city then boasted only 10 priests and 4 churches: Old St. Joseph's (founded by the Jesuits), St. Mary's (a new branch of that parish), Holy Trinity (for German immigrants fleeing the Napoleonic Wars), and St. Augustine (built by the friars of that order). 12 other churches fell in the diocese’s vast boundaries which covered all of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New Jersey. St. John’s would soon be built as a larger cathedral. Given the Hogan Schism recounted above, Kenrick immediately suspended Mass at St. Mary's until order was restored. By the next year of 1832, he established St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in his own residence (then on Fifth Street, between Spruce and Pine, now the site of CVS pharmacy) with the reception of the diocese’s first seminarian, Patrick Bradley, and two others, all from Ireland. All of this early history happened in what is today Old City and Society Hill.

II. St. Patrick's Church Established

In 1839, St. Patrick’s Church was established in response to Irish families moving west and working on unloading coal barges on the Schuylkill River and building houses along Manning Street. This was a good distance west of the city center, and it was commonly called “The Village” or going “Out Schuylkill.” It wouldn’t be until 1840 that James Harper built the first house on Rittenhouse Square itself (the 1811 Walnut Street mansion which stands to this day) thus inaugurating the movement of wealthy families westward. Previous to then, the square had been designated a park by William Penn but left feral as deer and fox hunting grounds, until the area was roped off and again left mostly for grazing cattle and chickens, surrounded soon after by clay pits and various company kilns for brickmaking.

It was the home of Paul Reilly, a local law clerk, which can rightly be called the foundation of our parish. One evening in 1839, he called together his Catholic neighbors to discuss forming a parish, and they at once petitioned Bishop Kendrick. Being Irishmen, they requested St. Patrick as the patron of their church. This was also an appeal to the bishop’s middle name of Patrick, seeing as he had recently founded St. Francis Xavier church just north of us which bears his first name. Their letter also uses the language of a “free church” with no rented pews for the wealthy (a common feature among city churches), and it suggested the church be located in Goosetown, slightly uphill from the river, so that it would sit among Protestant homes and less likely of being burned! Although anti-Catholic riots wouldn’t break out in Philadelphia until 1844, already the sentiment was in the air, especially since the 1834 convent burning of the Ursuline sisters in Boston.

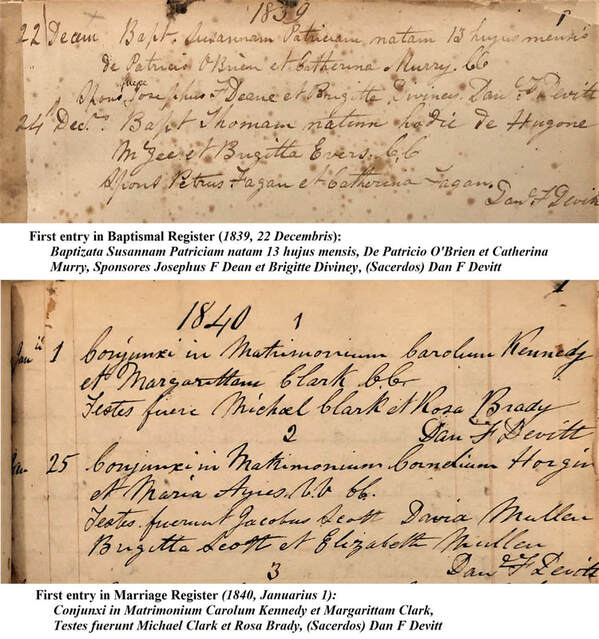

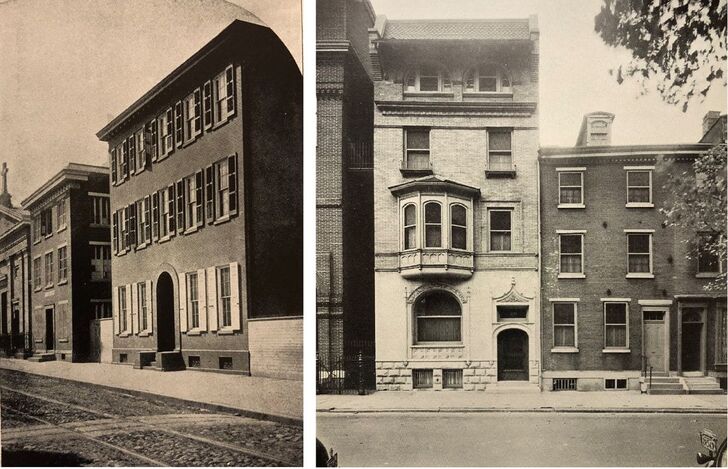

Soon, Kenrick leased a house on the east side of 19th Street, between Manning and Spruce (just north of what is today Marathon Grill on the Square). The house was an original U.S. Navy Yard home, whose frame had been transported by a man named Stephen Kingston across the city, the military base then being at Federal Street and the Delaware River. It had first operated as a carpenter's shop and vinegar factory, but on December 22, 1849, the first Mass in this new chapel was celebrated by Fr. Daniel Devitt.

It was the home of Paul Reilly, a local law clerk, which can rightly be called the foundation of our parish. One evening in 1839, he called together his Catholic neighbors to discuss forming a parish, and they at once petitioned Bishop Kendrick. Being Irishmen, they requested St. Patrick as the patron of their church. This was also an appeal to the bishop’s middle name of Patrick, seeing as he had recently founded St. Francis Xavier church just north of us which bears his first name. Their letter also uses the language of a “free church” with no rented pews for the wealthy (a common feature among city churches), and it suggested the church be located in Goosetown, slightly uphill from the river, so that it would sit among Protestant homes and less likely of being burned! Although anti-Catholic riots wouldn’t break out in Philadelphia until 1844, already the sentiment was in the air, especially since the 1834 convent burning of the Ursuline sisters in Boston.

Soon, Kenrick leased a house on the east side of 19th Street, between Manning and Spruce (just north of what is today Marathon Grill on the Square). The house was an original U.S. Navy Yard home, whose frame had been transported by a man named Stephen Kingston across the city, the military base then being at Federal Street and the Delaware River. It had first operated as a carpenter's shop and vinegar factory, but on December 22, 1849, the first Mass in this new chapel was celebrated by Fr. Daniel Devitt.

|

The first baptism took place during that Mass, that of Susanna Patricia O'Brien, who would later take the name Sr. Evangelista, I.H.M. and serve as a school teacher and local superior in neighboring counties. The first parish wedding was on New Year’s Day of 1840 between Charles Kennedy and Margaret Clark. By that fall, the house was opening on weekdays as St. Patrick’s School. In the 2 years that St. Patrick’s Church operated on this site, there are recorded 331 baptisms and 60 marriages.

Fr. Devitt, himself a Society Hill native, was only 23 years old and 3 months ordained a priest when named pastor of the new parish. He had taken Latin classes from Kenrick as a youth, and unlike the other Irish and English seminarians, he was the diocese’s first native vocation (and first native ordained priest). He was sent to study at the Urbaniana in Rome, which Kenrick had also attended. By then, it was not only a place of training for priests going to mission lands such as America, but also for seminarians coming from those lands, as in the case of Devitt. He returned to Philadelphia for ordination, Kenrick imposing hands upon him at the diocese’s second cathedral, St. John the Evangelist, then off he went down Schuylkill. He lived with Paul Reilly (mentioned above) until a rectory was built 6 years later in 1845. He also served in mission churches at this time. |

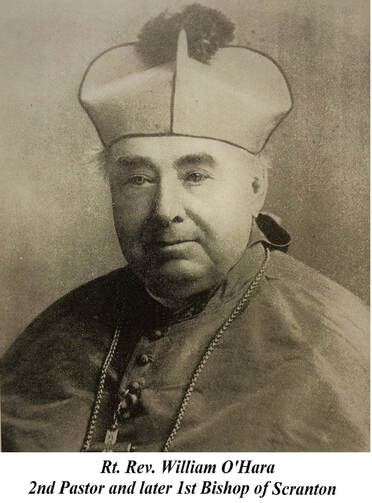

St. Patrick’s parish boundaries extended north to Vine Street north, to all of West Philadelphia as far as Overbrook, south along both banks of the Schuylkill River, and even extending through southern New Jersey as far as Cape May. Baptism records exist for Devitt’s journeys to 3 of the parish’s mission churches, in Leiperville (near Widener University) and also Port Elizabeth and Millville, NJ (the childhood home of MLB star, Mike Trout). He was assisted for a time by his seminary classmate, Fr. Joseph Ignatius Balfe, before he was transferred to full-time teaching at the seminary, by then located at 18th and Race Street, the same site of the present cathedral rectory. Two other priests would assist Devitt in the first years, both Fr. Andrew Gibbs and Fr. William O’Hara, later named the first bishop of Scranton.

St. Patrick’s boundaries were extended in 1841 to cover all of South Philly, much of which was a farming region. Our parishioner Glenn Johnson still remembers that his relatives, the Rogers family, operated a large farm on Broad Street near the present sports stadiums well into the 1950s. Over time, our boundaries would be reduced when more parishes were established: the north reduced to Market Street by the Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul, established 1849; the west reduced to the Schuylkill River by St. James Church, established 1854; the south reduced to South Street with 1880s Italian immigration to South Philly and subsequent building boom across the city; nearby neighborhoods were given to St. Charles Borromeo Church and St. Anthony’s Church, established 1868 and 1886. The first would later become a black Catholic community, while the second would be a poorer Irish parish and close its doors in 1999. To the west, we have always kept a similar boundary with St. John the Evangelist.

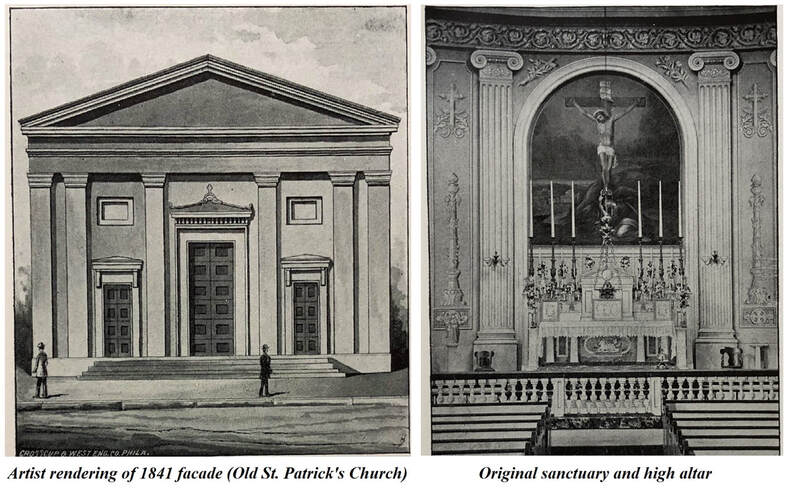

III. Old St. Patrick’s

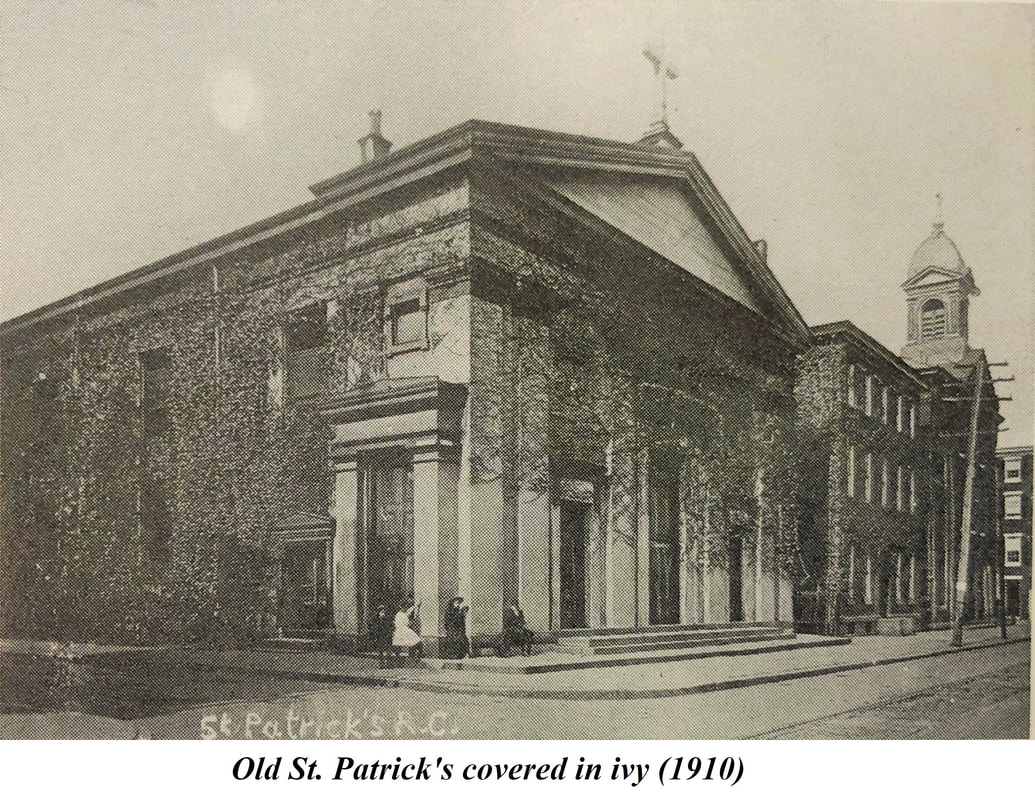

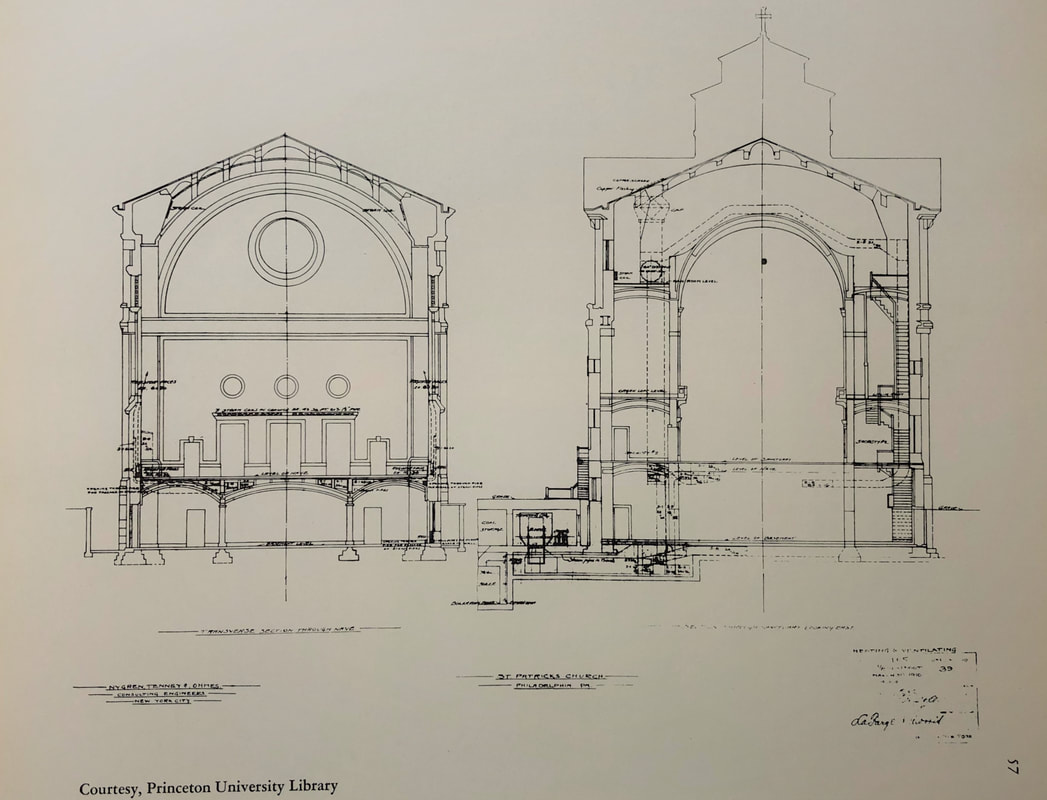

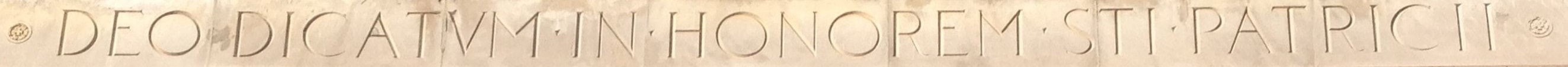

Still, in 1841, St. Patrick’s had no proper church. On June 1, Devitt finally purchased a new plot of land for $6,000 as a construction site of a proper church ($150,000 today with adjusted inflation), approved by a parish council meeting on June 5. A month later, the great celebration of July 4 saw the laying of the cornerstone by Kenrick, and a sermon was preached by Fr. Patrick Moriarty, O.S.A., who was a missionary to India and founder of Villanova University. A collection was then taken up among the crowd after the sermon! The building, measuring at 60x100ft, was designed in brick by Napoleon LeBrun, the same architect who would go on to build our present cathedral. LeBrun was a Philadelphia native who apprenticed under Thomas Ustick Walter, later to be the architect of the United States Capitol. After setting up his own office, LeBrun designed churches, courthouses and prisons in neighboring counties, and notably Philadelphia’s Academy of Music, still in use on Broad Street and home of the Pennsylvania Ballet and Opera. His first church was St. Philip Neri across town, which is still standing today and a great example of what our first church was like.

Old St. Patrick’s church, as it is now called, was quickly completed by December 5, 1841, a mere 6 months since the piece of earth on which it stood was purchased. It would take 23 years to pay the mortgage, reflecting the poverty of the parish in that age. Though dedicated, the church was far from complete, having no stained glass and no pews, but some benches alone for seating. That day, the prayer of dedication was made by Kenrick’s vicar general, Fr. Michael O'Connor, originally of County Cork: “Pour out, O God, Thy grace upon this place of prayer, so that all who call upon Thy name therein, may feel the effects of Thy mercy.” The Solemn Mass which followed was presided by Bishop Peter Lefebre of Detroit and preached by Kenrick’s brother, Peter Richard, his first homily as newly consecrated bishop of St. Louis. Sadly no record of that first homily exists. (These men’s paths in years ahead help give a sense of how missionary the American Church still was. O’Connor, for example, would become the first bishop of both Pittsburgh and Eerie, then resign to join the Jesuits in later life. His brother, James, was the first rector of the seminary in Overbrook and would become first bishop of Omaha.)

Old St. Patrick’s church, as it is now called, was quickly completed by December 5, 1841, a mere 6 months since the piece of earth on which it stood was purchased. It would take 23 years to pay the mortgage, reflecting the poverty of the parish in that age. Though dedicated, the church was far from complete, having no stained glass and no pews, but some benches alone for seating. That day, the prayer of dedication was made by Kenrick’s vicar general, Fr. Michael O'Connor, originally of County Cork: “Pour out, O God, Thy grace upon this place of prayer, so that all who call upon Thy name therein, may feel the effects of Thy mercy.” The Solemn Mass which followed was presided by Bishop Peter Lefebre of Detroit and preached by Kenrick’s brother, Peter Richard, his first homily as newly consecrated bishop of St. Louis. Sadly no record of that first homily exists. (These men’s paths in years ahead help give a sense of how missionary the American Church still was. O’Connor, for example, would become the first bishop of both Pittsburgh and Eerie, then resign to join the Jesuits in later life. His brother, James, was the first rector of the seminary in Overbrook and would become first bishop of Omaha.)

Societies soon began to spring up in the parish, dedicated to the Scapular, the Rosary, Our Lady of Mercy in service of the poor, and also the wordy but essential society of the Eucharstic League of the Sacred Heart. Finances, however, were tight. Various fundraising efforts were organized closer to center city at the Philadelphia Museum, such as a fair held in the Chinese Salon selling “articles beautiful and numerous, to aid St. Patrick’s Church out of its difficulties.” There were also ticketed lectures pitched to Hibernian societies, and Fr. Ryder, S.J. of Holy Cross College preached vespers with a collection to follow.

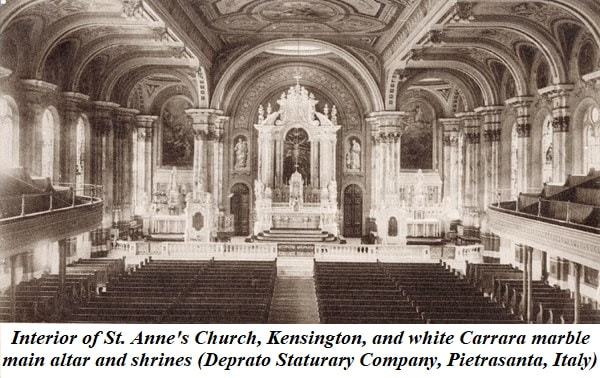

IV. St. Anne's Mission and Nativist Riots

St. Patrick’s was constructed during a 5-year depression known as the Panic of 1837, when national finance markets collapsed, due in large part to railroads springing up and leaving behind major investors in a growing eastern canal system, quickly abandoned and left unfinished. Locally, coal began to be transported by new railroads directly to Port Richmond, northeast of the city, bypassing the entire river barge system. Many parishioners, making their wage as dock workers, were now forced to either commute daily to the new site, or to move their families, as many indeed did. When the local Catholic parish, St. Michael’s, was burned to the ground by the Protestant Know-Nothing riots of 1844, Devitt petitioned the diocese to send another priest to found a mission church there. Told no priests were available, he himself took up the task of establishing yet another mission church.

He journeyed weekly to say Mass, first in a public school (by permission of a Protestant board member) until he then purchased a plot which was to become St. Anne’s church. The cornerstone was laid in 1845 by Very Rev. F.X. Gartland, the pastor of the cathedral St. John the Evangelist and later the first bishop of Savannah in 1850. Fr. Devitt continued as pastor for a year, until the diocese finally assigned Fr. Hugh McLaughlin.

A story is told of a couple knocking on the rectory door one night during a thunderstorm, May 18, 1856. Seeing that the woman was in labor, Fr. McLaughlin admitted them, and she gave birth to a boy. Though both parents were Episcopalian, they asked to have him baptized Catholic in honor of the pastor’s generosity. The mother soon died, and the father moved west of the city with his son, Samuel Vauclain, the future inventor of the Vauclain compound locomotive and millionaire president of Baldwin Locomotive Works, then the largest producer of steam locomotives. Fr. William Cambell, in drafting the 1965 parish history book for St. Patrick’s, recorded this story from an oral tradition he heard from an old man from Port Richmond, whom he calls “a reliable source in all my dealings with him.”

The present church of St. Anne’s was built later in 1870, a so-called “fortress of faith” and built low to the ground and with rooftop walkways, as better defense against any future attacks. Much of the interior decor was lost in a 1947 fire.

He journeyed weekly to say Mass, first in a public school (by permission of a Protestant board member) until he then purchased a plot which was to become St. Anne’s church. The cornerstone was laid in 1845 by Very Rev. F.X. Gartland, the pastor of the cathedral St. John the Evangelist and later the first bishop of Savannah in 1850. Fr. Devitt continued as pastor for a year, until the diocese finally assigned Fr. Hugh McLaughlin.

A story is told of a couple knocking on the rectory door one night during a thunderstorm, May 18, 1856. Seeing that the woman was in labor, Fr. McLaughlin admitted them, and she gave birth to a boy. Though both parents were Episcopalian, they asked to have him baptized Catholic in honor of the pastor’s generosity. The mother soon died, and the father moved west of the city with his son, Samuel Vauclain, the future inventor of the Vauclain compound locomotive and millionaire president of Baldwin Locomotive Works, then the largest producer of steam locomotives. Fr. William Cambell, in drafting the 1965 parish history book for St. Patrick’s, recorded this story from an oral tradition he heard from an old man from Port Richmond, whom he calls “a reliable source in all my dealings with him.”

The present church of St. Anne’s was built later in 1870, a so-called “fortress of faith” and built low to the ground and with rooftop walkways, as better defense against any future attacks. Much of the interior decor was lost in a 1947 fire.

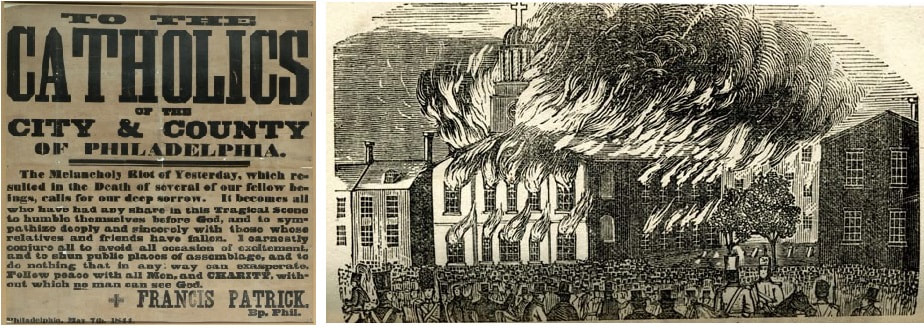

The 1844 Nativist Riots themselves were sparked by the 1837 establishment of the Public School System in America. Bishop Kenrick had requested from the city that Catholic students could use their own version of the Bible in class instead of the King James Version. This was approved by the local Whig party, but in response, a total of 94 Protestant clergymen joined together against this so-called Romanism. Animosity towards Catholics had already produced small incidents even in the neighborhood, as in the story told among parishioners that a bystander spat upon the cornerstone during its blessing ceremony in 1841. This spirit can be traced back to New England roots with the Adams administration, as well as the Second Great Awakening among many faith communities, a charismatic push in evangelical preaching, turning at times against neighboring Catholics. It’s worth saying, however, that the particular conflict Philadelphia was among Irish on both sides, the ancient Catholic-Orangemen divide from the old country revived here, as even the Protestant tune “Boyne Waters” was heard in the street those nights, along and cries of “to hell with the pope and O’Connell,” that is, Daniel O’Connell, the former Lord Mayor of Dublin who petitioned British Parliament for Irish Catholic seats.

The first riots broke out in the Kensington marketplace on May 6, provoked by a rally with preaching against “the influence of Popery and the miscreant Irish.” The rally soon turned into a mob, and fighting broke out when two Protestants were shot dead by Catholics from a nearby window. Gunfire was traded between men and women of both sides, which would claim 14 lives in a few days and injure over 50. Police were permitted by law only to operate within city limits, which then ended at Vine Street. Any activity north of there was left to state militia to handle. That first evening, militia did mobilize from the Wayne Artillery Corps, and with countless Catholic shops and homes in flames, about 200 families had fled west on foot down Jefferson Avenue until they reached the forest at 18th Street where they spent the night in the open. The next morning, a local judge asked Paul Reilly - the first man to petition Kenrick for a church and to house Fr. Devitt for many years - to organize St. Patrick’s parishioners in bringing relief to the families. So they arrived with carts full of blankets and food, continuing for many days. This site would providentially become the first Philadelphia convent of the Little Sisters of the Poor later in 1869.

Bishop Kenrick posted placards around the city to instruct Catholics: “I earnestly conjure you to avoid all occasions of excitement and to shut all public places of assemblage… Follow peace with all men and have charity without which no man can see God.” On the night of May 8, a crowd of rioters burned down St. Michael’s Church and the Sisters of Charity convent, then they moved south to burn St. Augustine’s Church, not to mention the library, school and friary, all ignited by a 14-year-old boy in the crowd. This transpired under the watch of the military police who stood by. Papers also noted how the mob threw rocks at the mayor, John Morin Scott, who was present, and how the crowd cheered when the church steeple fell. That site had ironically served as a hospital in the 1832 cholera outbreak, 80% of the patients being Protestant. “The next morning, passersby awoke to see the charred building burned away, with only a single painting above the place where the altar had stood: “The Lord Seeth.”

The first riots broke out in the Kensington marketplace on May 6, provoked by a rally with preaching against “the influence of Popery and the miscreant Irish.” The rally soon turned into a mob, and fighting broke out when two Protestants were shot dead by Catholics from a nearby window. Gunfire was traded between men and women of both sides, which would claim 14 lives in a few days and injure over 50. Police were permitted by law only to operate within city limits, which then ended at Vine Street. Any activity north of there was left to state militia to handle. That first evening, militia did mobilize from the Wayne Artillery Corps, and with countless Catholic shops and homes in flames, about 200 families had fled west on foot down Jefferson Avenue until they reached the forest at 18th Street where they spent the night in the open. The next morning, a local judge asked Paul Reilly - the first man to petition Kenrick for a church and to house Fr. Devitt for many years - to organize St. Patrick’s parishioners in bringing relief to the families. So they arrived with carts full of blankets and food, continuing for many days. This site would providentially become the first Philadelphia convent of the Little Sisters of the Poor later in 1869.

Bishop Kenrick posted placards around the city to instruct Catholics: “I earnestly conjure you to avoid all occasions of excitement and to shut all public places of assemblage… Follow peace with all men and have charity without which no man can see God.” On the night of May 8, a crowd of rioters burned down St. Michael’s Church and the Sisters of Charity convent, then they moved south to burn St. Augustine’s Church, not to mention the library, school and friary, all ignited by a 14-year-old boy in the crowd. This transpired under the watch of the military police who stood by. Papers also noted how the mob threw rocks at the mayor, John Morin Scott, who was present, and how the crowd cheered when the church steeple fell. That site had ironically served as a hospital in the 1832 cholera outbreak, 80% of the patients being Protestant. “The next morning, passersby awoke to see the charred building burned away, with only a single painting above the place where the altar had stood: “The Lord Seeth.”

Kenrick himself fled the city for a time, reserving the Blessed Sacrament in homes of the laity, and suspended all Masses “until it can be resumed with safety and we can enjoy our constitutional right to worship according to the dictates of our conscience.” Martial law was declared, with soldiers posted on every street corner. Dr. Thomas Perkins Stokes rode horseback to our neighborhood, asking St. Patrick’s to arm itself with muskets provided by the city. The married men of the parish kept guard around the church itself, while the unmarried men formed a first line of defense in Rittenhouse Square, a post they held for 5 days, to intercept any attempts against their own church. No further activity followed immediately, and the city gave compensation to help rebuild the two burned churches, until a second wave of the riots visited after the July 4 parade. A mob gathered outside of St Philip Neri church, where soldiers were stockpiling arms for their patrol of the city. Various exchanges transpired between the mob and the soldiers from July 5-8, with cannons being fired into the crowd, the mob retrieving their own cannons from the wharf and firing into the walls of the church, leaving at least 15 dead all in all, not to count many injuries. Philadelphia petitioned the federal government, and 5,000 troops were soon stationed in the city to keep peace. The violence had New York City also mobilize to guard their Catholic churches, and the whole issue was discussed nationally and cited as one reason James K. Polk would win the presidential race that year on the Democratic ticket, as the Whigs became associated with the riots.

V. A Saintly Bishop and a School at Last

For the next 10 years, St. Patrick’s Church would continue to grow, especially given the influx of Irish immigrants from the Great Famine, reaching it peak in 1847. The Sisters of the Good Shepherd arrived from Louisville in 1850, residing on 22nd Street, where Devitt and his assistants would celebrate daily Mass for them. For our parish history, this marks the beginning of a long history of cooperation between priests and sisters, to take new forms in coming years. These sisters stayed in the neighborhood for 30 years, and almost 100 girls from the parish would take their habit in that time.

By 1851, the church finally had proper pews installed, to handle the large Mass crowds. That year, Bishop Kenrick was named Archbishop of Baltimore and left the city in sadness. He would go on in 1853 to introduce the Forty Hours' Devotion in the United States, as well as poll the American bishops in 1854 concerning their support declaring the Immaculate Conception as dogma. He himself would attend the declaration in Rome later that year. The man we now know as St. John Nepomucene Neumann would replace him as Philadelphia’s fourth bishop, and the two traded places really, as Kenrick ordained him in Baltimore upon his arrival. He would spend the next 8 years in Philadelphia, until his untimely death of a heart attack on January 5, 1860, running daily errands on Vine Street. Born and educated in Bavaria, Neumann had been ordained at Old St. Patrick’s in New York, then after serving at parishes upstate, he applied to become the first vocation of the Redemptorists in the New World.

He was a mere 40 when he was serving as their provincial in Baltimore and chosen as Philadelphia’s new bishop, arriving in 1852 and soon consolidating the few parish schools into the first Catholic school system - St. Patrick’s included - with newly organized joint funding and regulations on curriculum and teacher salaries. (The year previous, Kenrick had given a speech proposing this idea at the Catholic Philopatrian Society, then held at the Athenaeum on Washington Square, but he had not enough time to implement it before leaving to Baltimore.) With the continual arrival of immigrants, schools numbered 200 by the time of his death, not to mention countless new parishes, completed at the rate of nearly one per month, many of them “national churches” which spoke only the language of their home countries. Neumann was a polyglot, able to speak English and German, as well as fluent Italian to that new community arriving in the city. In 1852, he founded St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi, the first national Italian parish in the U.S. The large wave from southern Italy wouldn’t arrive and fill most of South Philly until the 1880s. When these parishes were later consolidated, all hell broke loose, as when parishioners of Our Lady of Good Counsel took their own Augustinian pastor hostage for five months to protest the move. Neumann’s accent, however, endeared the local clergy more to his auxiliary, James Wood, and the bishop more than once wrote to Rome requesting the diocese be split and he himself take the rural portion and be rid of the city.

The fall of 1852 was the opening of St. Patrick’s school proper, with a brand new building completed that summer. (For those familiar with St. Patrick’s buildings today, imagine the same order of buildings on our block beginning from the south - church, rectory, then school - only that all 3 original edifices were much smaller than the present ones, occupying half of the block, compared to our full block stretch today.)

St. Patrick’s School had begun in 1840 in the first parish house, a small operation run by 3 lay teachers, Mr. Daly, Mr. William Jennings, and Mr. James Cullen. All except Daly would enter seminary for the priesthood. This arrangement only lasted a year, until all funds were put towards building the church proper, and 60 or so students all moved for the next decade to the local public school called “Woods” on 23rd and Lombard Streets. That is, until they were one day collectively expelled! In May of 1849, all Catholic students had missed class on Friday because of participation in the parish May Crowning procession, the crowning itself of the Virgin Mary statue being carried out by an 8th grade girl in her role as “queen” that year. On the following Monday, the principal called an assembly at the start of the school day, she read select verses from the Bible against the honor of Mary, then declared summarily to all the Catholic students: “The queen and her train may now go forth.”

That spring, a parish meeting was called, and it was decided to build a new parochial school. It would be the second one in the diocese after St. Mary’s in Society Hill. Opened in September of 1852, the 3-story building received 600 students that first year! (The reader should remember the immigration comments above. Newspapers also commented that the students were poor.) At the start, there were 13 lay teachers, all women, paid $150 yearly salary ($4,669 today with adjusted inflation), as well as 2 principals and 2 priests, Fr. Flood and Fr. Rice, to teach the older boys. The building also doubled as a parish hall on the ground floor, which became known as a place of receptions, as well as lectures by various journalists, the Fr. John McCaffery, president of Mt. St. Mary's College, and the famous New England convert to the faith, Orestes Brownson.

The following year, the Belgian community of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur would open the doors of their larger academy for girls on Rittenhouse Square, attracting St. Patrick graduates over the next century. They were part boarding school and also had a co-ed grade school for children from high rise apartments and others who commuted for a private school education. When Sr. Julia, the superior of the community, went to the law office to sign the deeds of the new property, she and Sr. Marie Antonie dressed in disguise as elderly widows. The owners unsuccessfully tried to prevent the building of the convent when they later discovered the sisters’ identity, that Catholic sisters would dare claim a place on Rittenhouse Square. To a degree, Sr. Julia understood them. As a girl in Cincinnati, she had laughed at the habits of the first European sisters who arrived at her school, and now she laughed in telling of her own antics.

After inspecting the construction in her own meticulous manner, the sisters at last moved all of their furniture across town into the new convent, only to find that no front door had been attached. They barricaded the door with furniture and trusted in God's providence to protect them that first night in the neighborhood. For the next 100 years, St. Patrick’s priests would arrive with an assigned altar boy to celebrate 7 a.m. morning Mass in the sisters’ chapel, in addition to presiding at all Masses for the students’ sacraments, their May Crownings, graduations, and the like.

Next door to the school and convent was a mansion soon purchased by the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Alexander Cassatt, famous for tunneling under the Hudson River and into Manhattan without prior permission, hence the name Penn Station. His sister also lived there in stages of her life, the impressionist painter Mary Cassatt. Both buildings were sold in the late 1960s to build the Rittenhouse Hotel, and the sisters moved to their other campus in Villanova, still operating today.

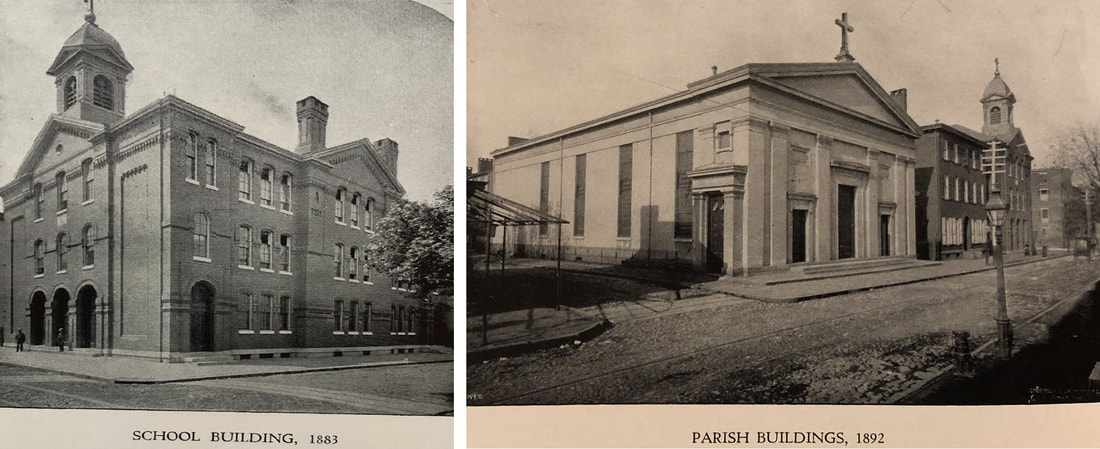

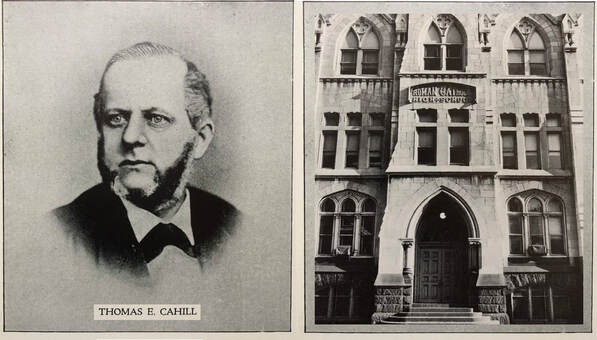

1865 was also the year that the Christian Brothers were invited in to teach the boys’ sections. Immigration continued, and by 1883 a new school, designed by Edwin Forrest Durang. Its ground floor served as the new parish hall, and combined with the upper floors it was built to accommodate 850 students. Idyllic as this may sound to modern ears, no time has ever seen human nature behaving perfectly, especially in attendance! Every fall had 2 weeks of open enrollment for classes due to so many late arrivals after summer, prolonging every teacher’s introductory classes. The opening of the new school was accompanied by an announcement of the pastor at all Sunday Masses: “We hope that Catholic parents will think of this and burden their consciences with the responsibility of having their children present tomorrow, the first day of the new school year.”

|

In 1922, the Christian Brothers were recalled by their superior after 57 years of service, citing lack of vocations and a priority to focus on serving in high schools. The entire Sunday collection was given to them as a parting gift, and the school building was majorly renovated the same year. Yet more Sisters of St. Joseph would replace them, staying on until their departure in June of 1971. Exactly twice the length of the brothers’ generous stay, the sisters completed 114 years of service here at St. Patrick’s, teaching the faith and all other subjects to countless children. This number, actually, can indeed be counted, as our school was joined with St. Mary’s in an interparochial merger, and all of its records are kept in the basement there to this day. (St. Mary’s is called the “mother school of Catholic parochial education,” as in 1782 it became the first English-speaking Catholic school to open in the Colonies.) The sisters’ farewell was announced in a letter from mother general to all parishioners at Masses on December 8, 1970, and once the school year came to a close, so also did the school itself. Every invitation for a major parish event began with the heading: “The priests, sisters, and parishioners of St. Patrick’s invite you…” Their place next to the priests shows how much they belonged to the parish, how irreplaceable their part was, and how everyone thought of the sisters when they thought of St. Patrick’s at all.

|

Parishioners today remember the decades of the 1950s and 60s well and the sisters who taught them. Strict though they may have been, it is told also of a funny policy of students being dismissed at the end of the day either to 20th Street, or for those who lived down Locust Street, exiting through the sisters’ attached convent and catching a glimpse of their dining room on the way out. Each student was still expected to attend the 9 a.m. Children’s Mass, with simpler music, a homily focused on them, and the expectation that each child would tithe in the basket with their own envelope! Previously, at the turn of the century, the girls’ school choir had become well known for singing sacred music. Most girls attended Notre Dame Academy upon graduation. Boys who graduated went on to attend a regional Catholic high school. A real rivalry existed among our students and those who attended St. Anthony’s just below South Street, with our students being labeled as “rich kids” though that was seldom the truth. Class sizes by this era had been reduced to about 10-12 students per grade until the closure.

VI. Devitt Goes West and The Old Doctor Steps In

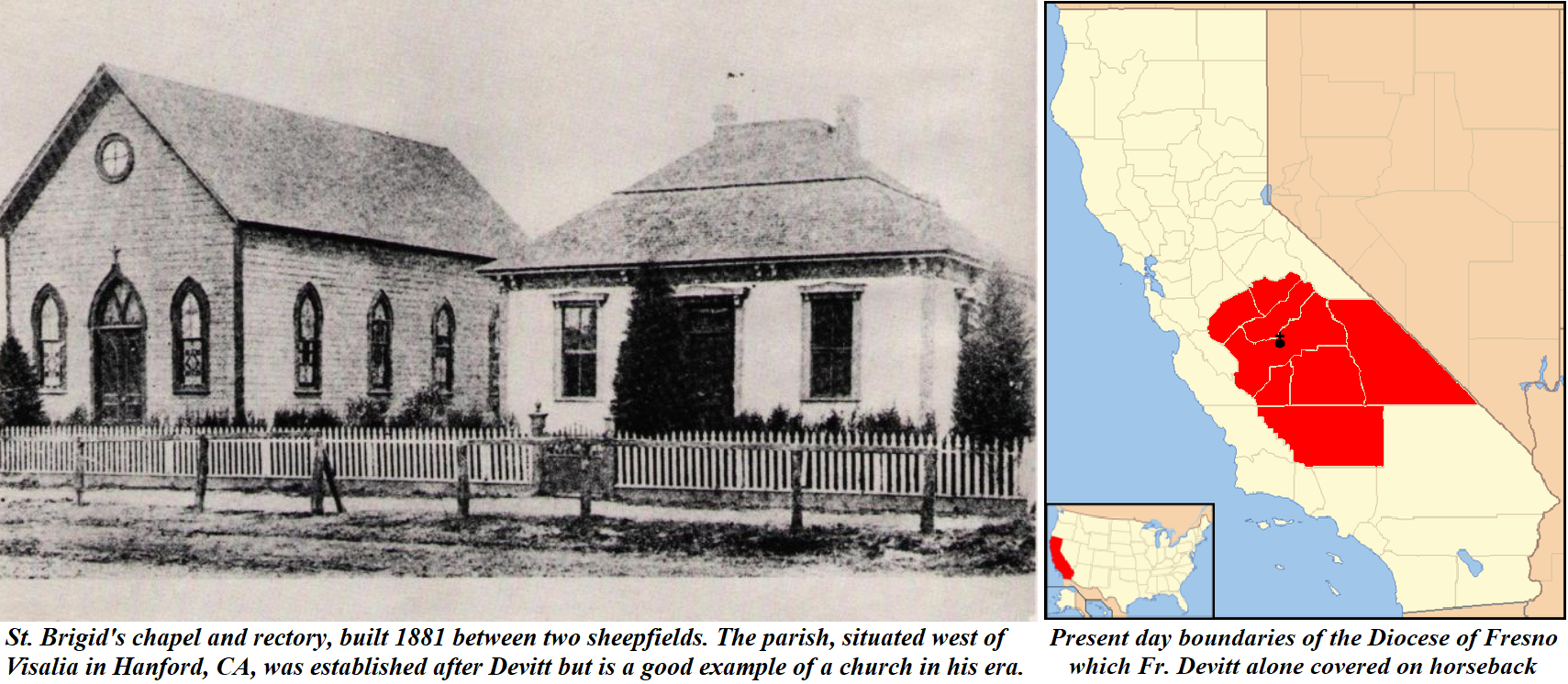

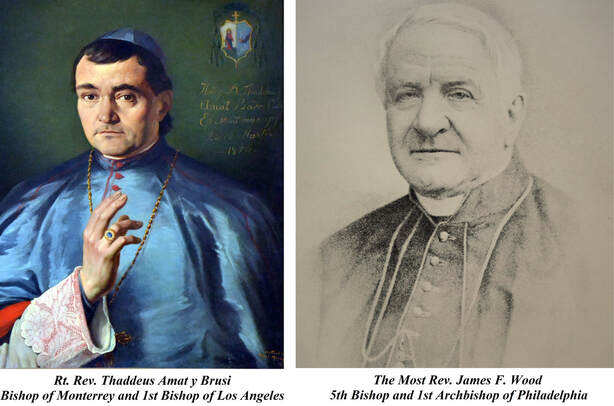

Returning to the 1850s growth period, it was in these days that the only pastor our parish had known, Fr. Daniel Devitt, resigned his post in the spring of 1856 to follow the California gold rush. They needed chaplains, and given his poor health, he was invited out by his Vincentian friend Thaddeus Amat, C.M., Bishop of Monterrey and previous rector of St. Charles Seminary. For reasons not documented and in Jason Bourne style, he began to use an alias and was called Fr. Francis Dade, perhaps easier to pronounce by Chicanos who had intermarried with Irish settlers. After a short stay in Santa Barbara, he was transferred to the village of Visalia in 1861 and founded Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church, commonly called St. Mary’s. The earliest Masses held in Visalia were those in 1859 by Fr. Francisco Mora, visiting as pastor of Mission San Juan Bautista. He departed after a 3-week attempt to establish a church there due to the small number of Catholics. Devitt lived in a stable initially and founded the church and an elementary school, as well as organizing the rebuilding efforts in Visalia after the great flood of 1862.

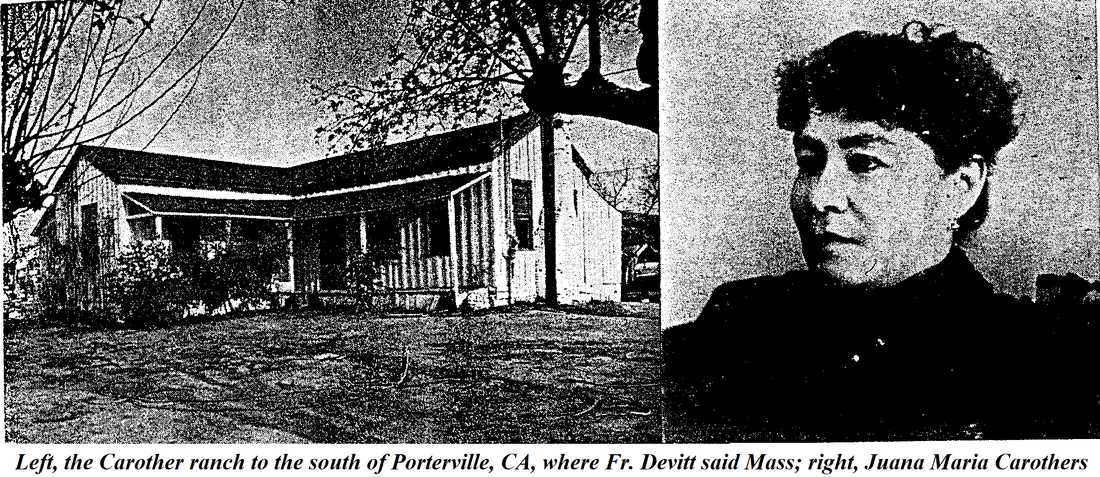

The next 11 years he rode a spring and summer circuit on horseback as the lone priest covering a territory of mission churches spanning 34,200 square miles, about a quarter of the entire state of California, which is today the Diocese of Fresno. In all, he served a Catholic community of about 20 families, though many non-Catholics attended his sermons at mission churches. His spring and summer circuit riding led to founding Saint Anne's Parish in Porterville, CA, in 1859 when he would celebrate Masses at the ranch of Samuel and Juana Maria Carothers, southeast of the city in Deer Creek. The parish history reads: “Father Dade would travel on horseback or by horse and buggy and spend two or three days at the Carothers ranch. During his visits he would celebrate Mass, provide religious instruction, visit the sick, validate marriages and baptize. These were "Fiesta" days when the many workers at the Carothers ranch would join the family in the religious observances. Celebrations would continue with roping and riding competitions, games, dancing and feasting. At the end of the visit Father Dade would travel to Havilah, then the seat of Kern County.” Bishop Amat even conferred Confirmation at the home one year. Devitt also said Masses at the Gilligan home, west of the city in Woodville, then called "Irishtown," on his way south to Deer Creek in those days.

Devitt retired due to poor health in 1872 and moved south of Eureka to Rohnerville, CA, where the Precious Blood Fathers has built a novitiate to train seminarians. He taught there briefly until his death in 1874, and his body was returned to Visalia for burial. A 1947 biography was written of him, Apostle of the San Joaquin Valley, by Sr. Mary Thomas, O.P., of the Kenosha Dominican Sisters. The community today is headquartered near Milwaukee, but first arrived to teach at a school in Oregon, and their second outpost was in Hanford, CA, just 20 minutes west of Visalia.

By the early summer of 1856, Fr. William O’Hara was named our second pastor, having already served here as an assistant for 13 years. During those years, he was also teaching at St. Charles Seminary on Race Street, where he was also made Rector. He retained that position even once he was made pastor. Born in County Derry, he was 4 years of age when his family immigrated to Philadelphia. He was later educated at Georgetown, and like Devitt he completed seminary in Rome at the Urbaniana. Once named pastor, Bishop Neumann held the priestly ordination of 6 men at St. Patrick’s that August, to honor parish. When Neumann died just more than 3 years later, his requiem Mass on January 9 was at the cathedral, St. John’s, out of which he was buried. His second closing requiem Mass - called the “month’s mind Mass” - was held 30 days later on February 8, 1860, at St. Patrick’s, with his successor Bishop Wood reciting the same requiem prayers and offering final absolution over his catafalque. (James Wood was a convert from Unitarianism and would be the first archbishop.) The saintly bishop had just celebrated a Solemn High Mass for St. Patrick’s day the year before in March of 1859. He had also celebrated Confirmation here on four different occasions, the number of children averaging 2-300 each time. At his beatification in 1963, the 250 or so names of the 1852 class of children were published in the monthly calendar (where parish news was printed before the advent of weekly bulletins). Though the sacrament is the same for all who receive it, nonetheless it’s a great thought to think how many children of the parish were walking about with the sacred character of confirmation bestowed on them by a saint! They, however, wouldn’t boast about it to other classes of students. No one of that generation lived long enough to see Neumann’s cause for sainthood reach its goal.

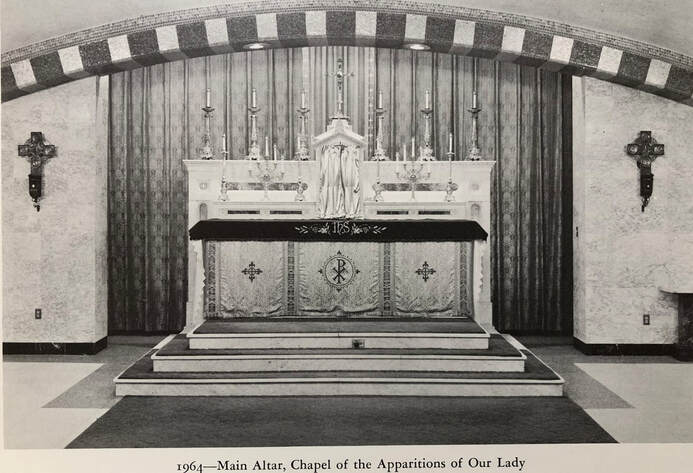

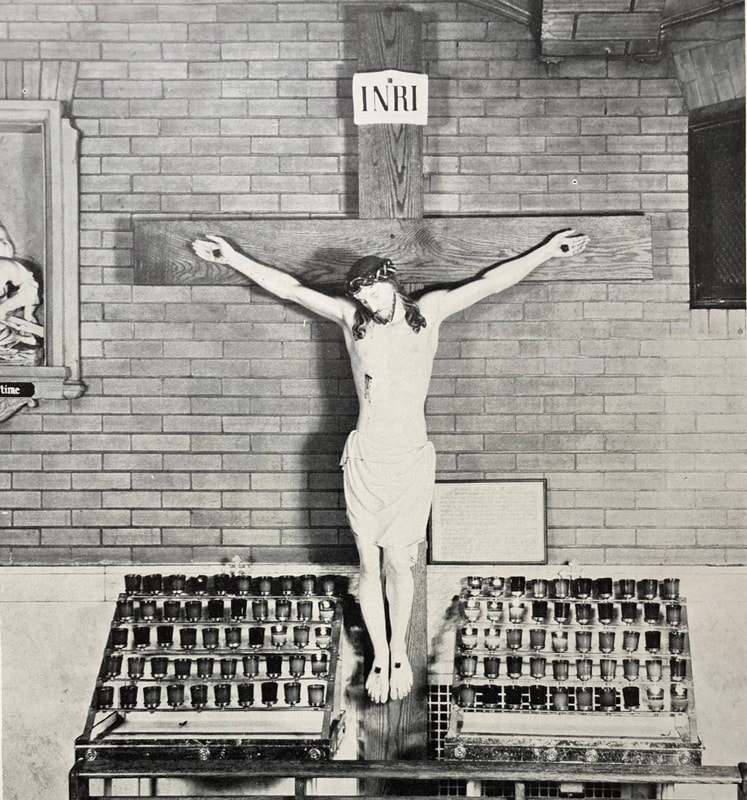

During his tenure, O’Hara would expand the sanctuary of the church in 1857, then adding skylights to brighten the space. It was he who invited in the Sisters of St. Joseph and the Christian Brothers to staff the school, while one of his faithful assistants Fr. Nicholas Walsh would make daily visits as chaplain to the school. In the spring of 1860, more windows were added to the church to increase light, the sanctuary was renovated, and the altarpiece re-painted, from the original crucifixion scene to a depiction rather of Our Lady as the Immaculate Conception, no doubt in light of the 1854 dogma declared by Pope Pius IX. (Later on in 1867 was added the first Italian marble altar in Philadelphia, surviving today as the altar in our lower chapel.)

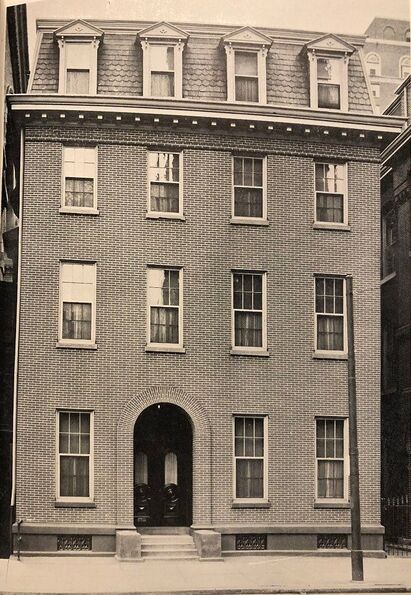

By July of 1860, the clergy moved into a new rectory, which is the same rectory standing today, except that it was first situated on the north corner of the property, 20th and Locust Streets. Its design is by Durang, the same architect who built our first school. The old rectory between the church and school, deemed dark and musty, was torn down. In 1863, the school was renovated, and a new organ of 1,800 pipes would be built in place by J. C. Standbridge company for the cost of $3,500 ($74,000 today with adjusted inflation). With all of these improvements, expenses came from donors and fairs, as well as ticketed lectures, such as one by Fr. Moriarty, O.S.A., who had preached at the laying of the cornerstone, now serving as Augustinian provincial. As the Civil War was sweeping over the land, he spoke to a packed crowd of 4,000 at Academy of Music, seated almost to the roof itself, on “The Flag of the Nation and the Cross of the Church.”

VII. The CiVIL WAR

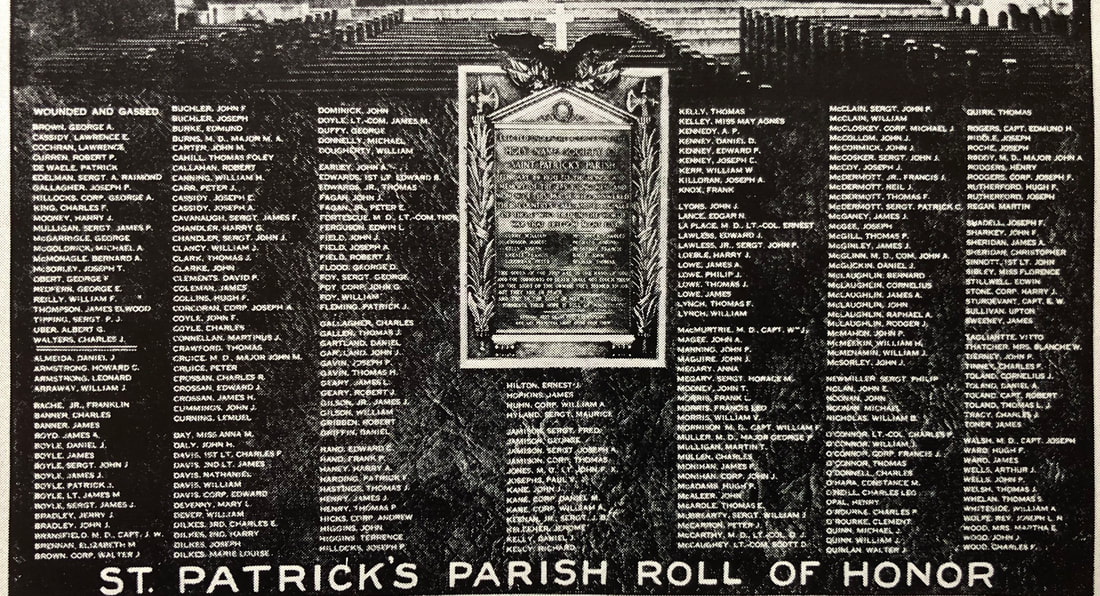

The Civil War years in Philadelphia saw the Irish joining in the 69th Regiment Infantry, originally composed of New York National Guardsmen, of which our men became the majority. They were nicknamed the “Fighting Irish” or simply the “Irish Brigade,” given to them by others not out of pride but derision. A total of 1,715 St. Patrick’s men fought in the war. The first group of recruits to leave, according to an eye-witness Edward Harley, attended morning Mass in common and had breakfast at the nearby restaurant The Malt House. They would take part in nearly all the major battles of the war, from Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, then north to play a central role repulsing Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, and south again to take part in Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and even the surrender of Lee at Appomattox Court House.

In all, the war would claim the lives of 291 men, with 184 captured or missing, and 346 wounded. Years later in 1889, Colonel James O’Reilly spoke at the dedication of the Gettysburg monument, remembering his men’s willingness to sacrifice, their obedience to orders, and the sad treatment they continued receiving as Irish returning back home:

“There are some here today who can look back with shame and sorrow, to the time when hisses and shouts of contempt were freely bestowed upon us, and on more than one occasion something harder, bricks or stones, fell thick and fast on the ranks of the organization is it marched through the streets of that city - the city of brotherly love.”

O’Hara shepherded his people through the war years, and new parish societies flourished which focused on doctrine and literature, as well as an altar society and continual service to the poor. Himself a G. K. Chesterton of sorts, O’Hara taught theology yet had a love for the common man, the workmen, the children, and especially the poor. And all who knew him, knew this about him. He was affectionately called by all “The Old Doctor.”

In 1867, parishioners organized a banquet to thank him for a quarter century of dedication to their church. After being presented with a check and enduring many speeches, he himself arose to speak: “Your compliments given to my years of labor among you are well calculated to embarrass me!”

“There are some here today who can look back with shame and sorrow, to the time when hisses and shouts of contempt were freely bestowed upon us, and on more than one occasion something harder, bricks or stones, fell thick and fast on the ranks of the organization is it marched through the streets of that city - the city of brotherly love.”

O’Hara shepherded his people through the war years, and new parish societies flourished which focused on doctrine and literature, as well as an altar society and continual service to the poor. Himself a G. K. Chesterton of sorts, O’Hara taught theology yet had a love for the common man, the workmen, the children, and especially the poor. And all who knew him, knew this about him. He was affectionately called by all “The Old Doctor.”

In 1867, parishioners organized a banquet to thank him for a quarter century of dedication to their church. After being presented with a check and enduring many speeches, he himself arose to speak: “Your compliments given to my years of labor among you are well calculated to embarrass me!”

Because of the poetic and sincere quality of his words, we will quote more of him. He spoke of the parish, calling it “a little grain of mustard seed which has sprung up to a great overshadowing tree, due to the fertility of the soil in which the seed was cast,” a reference to the people themselves. “For 24 years, I have been among you: how calmly, how sweetly, how rapidly those years have glided by, it’s beyond my power to explain. Here I celebrated my first Mass on returning to these shores. Here my lips were first opened to announce to the faithful the words of saving truth. Here I first administered the sacrament of Baptism. Here the first couple stood before me to be united in the bonds of holy wedlock. From this spot I was first called to impart to the dying the last consolations of our faith. Here, in a word, I entered upon my career in the labors of the Lord’s vineyard, and remained to the present, and here I hope to have the happiness to bring it to a close. Happy indeed have been my days among you, days abounding in that wealth beyond all price, the wealth of heavenly consolation.”

VIII. Two New Pastors, A New School, Death in Egypt

The parish and school were complete. The priests had a home to live in. The war dividing the nation was done. Then in the following year of 1868, Fr. O’Hara was named the first bishop of Scranton where he would serve the next 20 years until his death. He would not spend the rest of his days at St. Patrick’s, but he would return every March on the feast day to celebrate the Solemn High Mass. At his July 12 episcopal ordination, Fr. Michael O’Connor who had originally dedicated the church preached the sermon: “I have always admired your devotedness to the most humble and comparatively obscure duties of the ministry; your love and zeal for the poor; your priestly bearing; your unwearied perseverance in every good work.” This great man sang his first Pontifical Mass as a bishop at St. Patrick’s, then he went on to work in other areas of the Vineyard of the Lord.

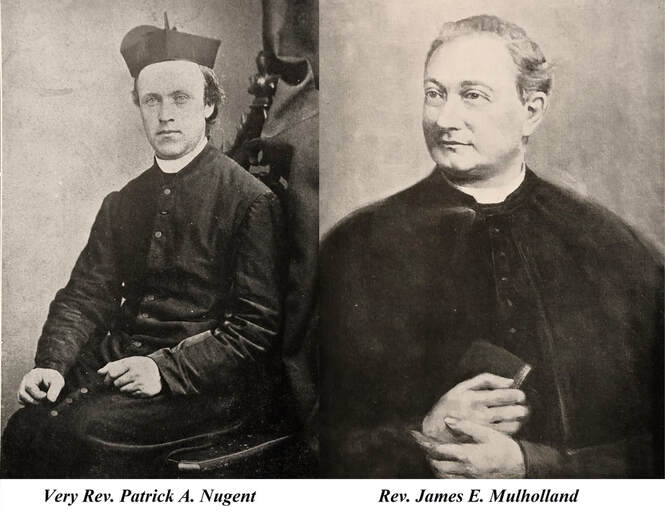

On October 1, 1868 Fr. Patrick Nugent was named our third pastor. Raised in Northern Ireland, he completed his studies at St. Charles and was the current pastor of St. John the Baptist in Manayunk when he received this news. As a matter of fact, physically, he was in Europe, seeking to recover from poor health. He arrived at St. Patrick’s, served for 7 months, then resigned and returned to Europe for health reasons. There he would serve for the next 22 years as chaplain to a monastery of French nuns.

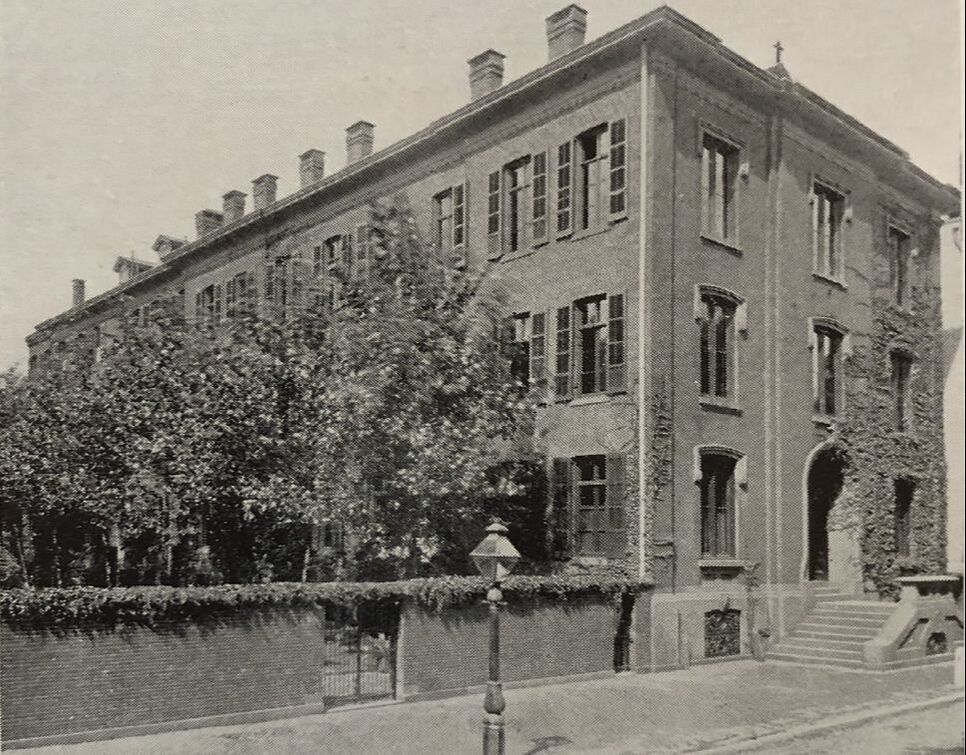

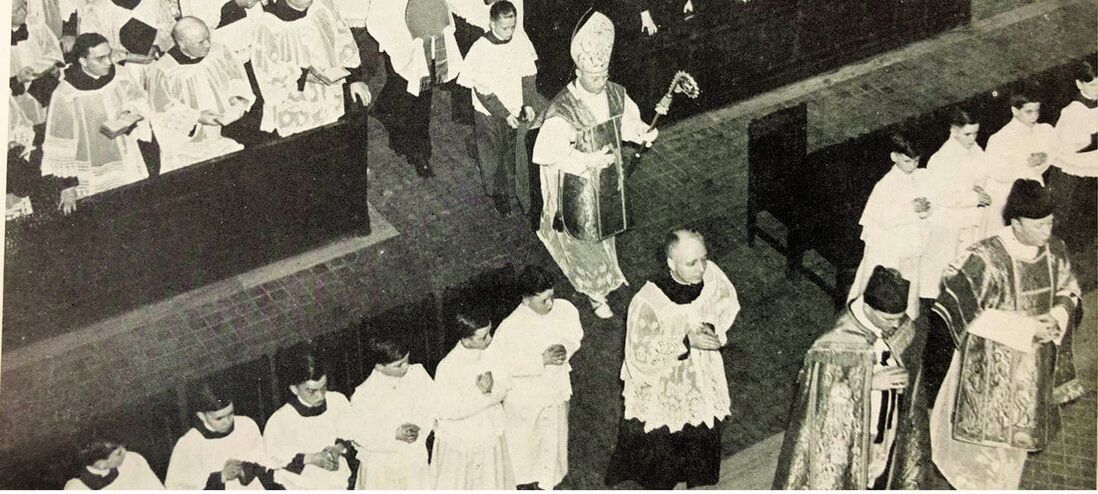

In May of 1869, Fr. James Mulholland was named our fourth pastor, also of Northern Ireland. He arrived in Philadelphia as a child and grew up at St. Philip Neri parish, completed seminary at St. Charles, and had his first priestly assignment under O’Hara as St. Patrick’s. After transferring among other parishes he now returned, and in 1871 he invited O’Hara back for the honor of consecrating Old St. Patrick’s Church. This ceremony occurs only once all church debt is paid, and it involves a ritual knocking at the front doors, a sign of the cross banishing all evil, writing the Greek and Latin alphabets in ashes on the floor, then sprinkling the altar with a mixture of water, salt, ashes and wine. The walls of the church are then blessed with chrism in 12 places and candles lit to mark each spot, marking it forever as a place of worship. The Old Doctor preached on the psalm, “How lovely is your dwelling place, Lord God of hosts,” a place he had helped beautify with plaster and paint, with preaching and prayers daily with the people.

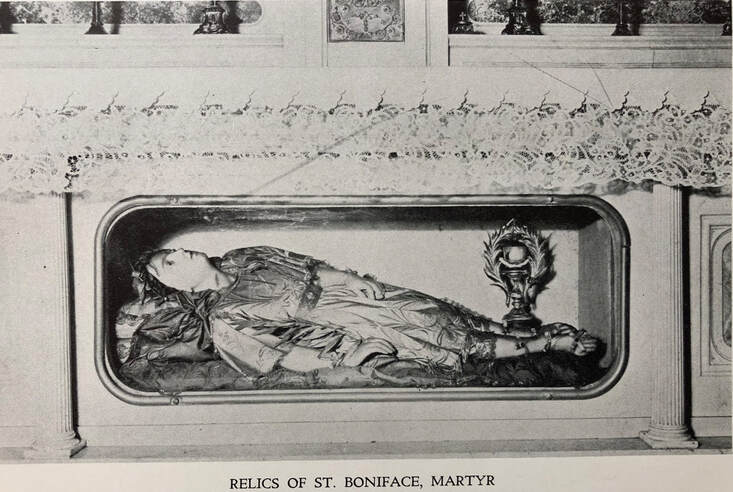

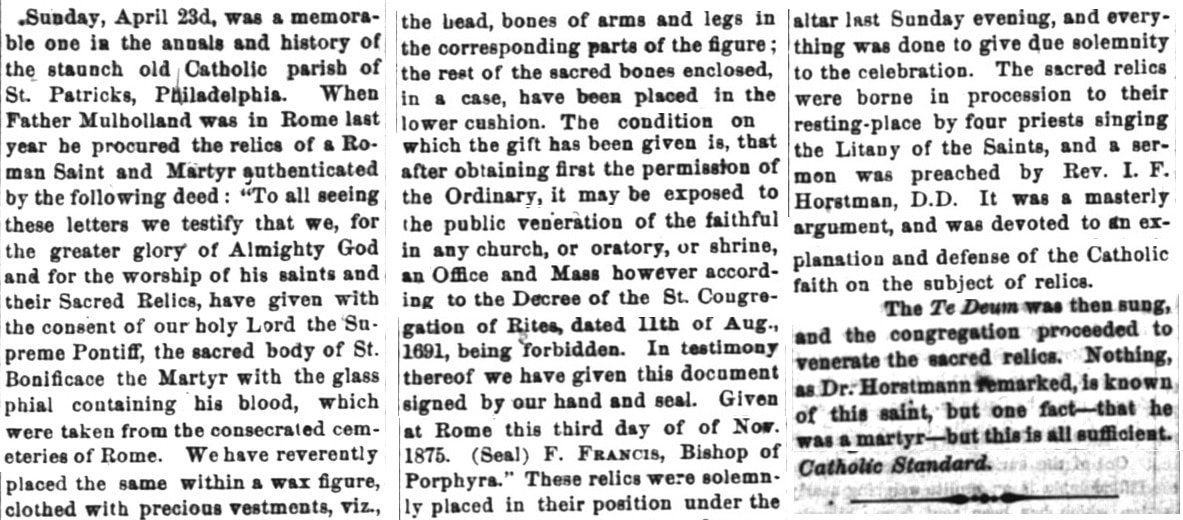

Mulholland too would add beauty to the church in years to come. Visiting Rome in 1875, he would acquire the full relics of an early Roman martyr, St. Boniface, then enshrined in St. Patrick’s main altar behind a glass cover. (There are 9 different saints by the name of Boniface in the Roman Martyrology.) Fr. Ignatius Horstmann, the future Bishop of Cleveland, was Mulholland’s closest friend from seminary, and he preached a sermon at the installation ceremony. The details were recounted in an article from the Catholic Standard Times.

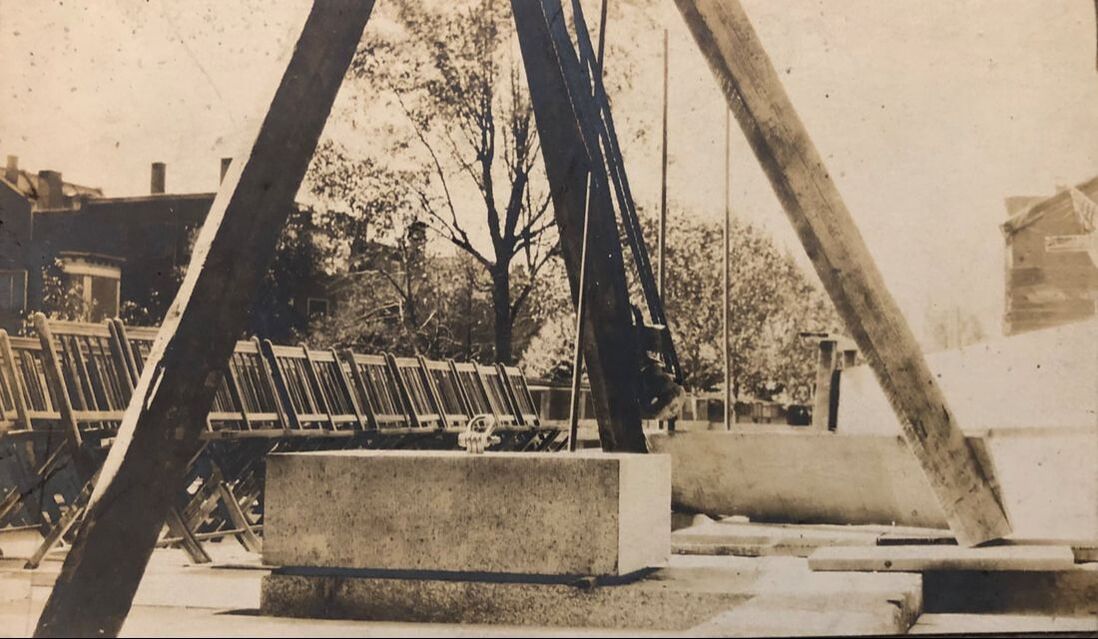

Later in 1885, the church at last received stained glass windows, interior frescoes, and a new sacristy. More societies would develop under his care, and as mentioned above, our present school building was built under his guidance in 1883. To do so, the old school beside the church was demolished, students transferred to a rented building at 2134 Lombard Street, and the rectory itself was moved a half block south to the former school site. This was a two-day process supervised by John Hughes out of Jersey City. It takes such men from such a state to move a 5,000-ton building intact. So slow was the move to its new foundations, it is said that the priests and secretaries carried on their normal daily business within the rolling edifice. Once situated, a back addition was added to the rectory.

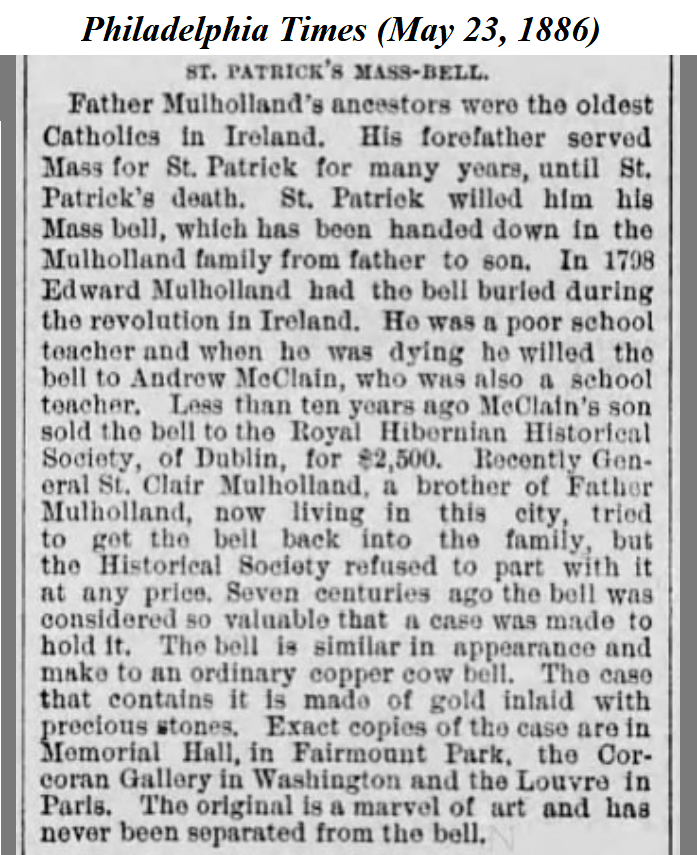

A quiet man by nature, Fr. Mulholland was described as one who would speak little, unless the subject of liturgy was raised, at which point he would speak eternally. He served as master of ceremonies for many liturgies throughout the diocese, by then the second largest in the United States. On May 7, 1886, after 17 years as pastor, a strange and sudden telegram arrived from Alexandria, Egypt that he had died sitting at the breakfast table.

|

He had been traveling with 2 priests from the Baltimore cathedral on a worldwide spree. After passing through Japan, he was bedridden in Hong Kong for 7 weeks with a swollen foot, injured years before by scaffolding which collapsed during a consecration. Afterward the party continued to India, then the Holy Land. It was said that horseback riding there had fatigued him, aggravating his underlying rheumatic heart condition, and soon he died, his requiem Mass hastily said by the Egyptian Franciscans. The incident was announced that evening to parishioners gathered for the May devotions. He was survived by half-siblings in County Antrim, a sister named Mrs. Louise Marie Gartland who lived west in St. Francis de Sales parish, and his older brother St. Clair Mulholland, Major General in the Union Army and recipient of the Medal of Honor for bravery at Chancellorsville. A month later, the pastor’s embalmed body arrived back in the States. Fr. McCabe traveled to New York to receive it and accompany it to Philadelphia where a Mass was offered for him. A burial vault was proposed by the parish council, to be located beneath St. Patrick altar, but Archbishop Ryan had denied the request as it was not customary. The body was instead buried across the river at Old Cathedral Cemetery in West Philadelphia. No sermon was preached for him, per the request in his will. |

To give an idea of parish demographics, Mulholland had undertaken a parish census upon his arrival, back in the summer of 1869. The results: 1,645 families, 8,361 persons, 528 baptisms, and 130 marriages. Catholics today may be tempted to think past days were glory days. In some aspects that may be true, but in others not. We were recently contacted by a family doing ancestry research, regarding an Irish couple and the baptism records for their 11 children through the 1860s. A good Catholic family. The records were each located, photographed, and sent back to the family, only for them to reply that other records show the wife marrying when she was, let’s say, far below the legal age, and the father later dying of alcoholism in a Philadelphia house of corrections, just shy of his 50th birthday. The Irish were a believing people, courageous also in war, and generous also in giving teetotalers a good reason to one day push for full prohibition.

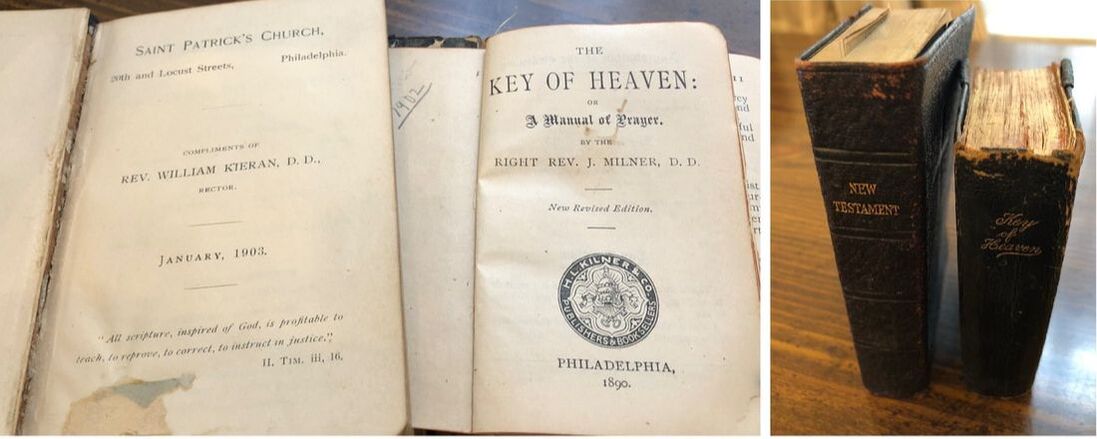

IX. Parish Societies were the only Society

Today, we speak of parishes having groups, whereas in the 19th century men and women similarly organized societies. The Total Abstinence Society was St. Patrick’s largest society of all. Established even before the church in 1840, as a response to a letter published by Kenrick, members had forsworn drink and kept safe their pledge cards, husbands and wives both, as on older parish history from 1892 says, “Some of the older members of the parish have always been doughty champions of the cause.” Michael Heffernan even boasted about pledging to the famous Fr. Theobald Mathew himself, while kneeling on the floor of Independence Hall. James Carr boasted instead that unlike the others, his pledge card was marked on Christmas Day 1840, the first group making their oaths in the original row house.) By 1873, Fr. Mulholland had reorganized the society and joined it to national union. In 1888, a women-only branch formed and became the largest of all, with a girls’ group to follow in 1891. By 1903, the Patrician Cadets were formed by Fr. William Currie for boys ages 16-21. It was popular, counted at 225 members, who would become involved in lectures, picnics, theater, and sports, before they came of age to join the men’s union.

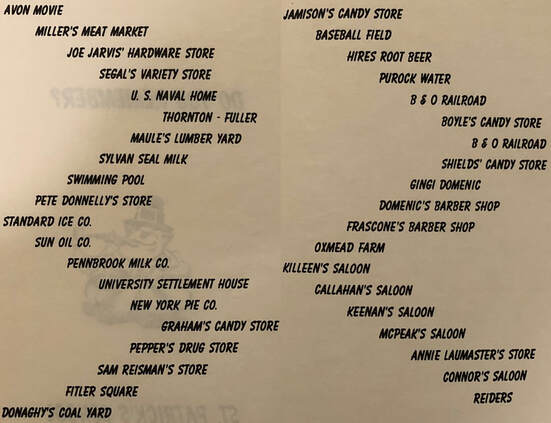

It’s funny to think about today, that instead of a parish youth group, any teenager had to swear off alcohol to be involved in anything at all! The pledge lasted until they were of age, and then they were encouraged to make the pledge for life. This was well before prohibition (1920-1933), and the spirit lasted well into the 1960s when Stephen Paisani of Epiphany parish remembers his 2nd grade class taking the pledge before First Communion and Confirmation that year. They also would take a yearly pledge in the Legion of Decency to never watch bad movies. Still, the 20th century saw a growing acceptance of bar culture for both men and women. Killeen’s on 26th and Pine Streets was for the old-timers, with a sliding window into the owner’s kitchen next door, and still seen with a separate ladies entrance where there was table seating. Other places had co-ed mixing, like McCoy’s bar (later named Gavin’s) on 2400 Lombard Street, which today is Rival Bros coffee, as well as Callahan’s at 2615 South Street, still in service and known back in the day for their weekend piano player and various singers. Like people today identify with their college sports team, men of the past identified with their bar, whom they represented in the summer softball league.

It’s funny to think about today, that instead of a parish youth group, any teenager had to swear off alcohol to be involved in anything at all! The pledge lasted until they were of age, and then they were encouraged to make the pledge for life. This was well before prohibition (1920-1933), and the spirit lasted well into the 1960s when Stephen Paisani of Epiphany parish remembers his 2nd grade class taking the pledge before First Communion and Confirmation that year. They also would take a yearly pledge in the Legion of Decency to never watch bad movies. Still, the 20th century saw a growing acceptance of bar culture for both men and women. Killeen’s on 26th and Pine Streets was for the old-timers, with a sliding window into the owner’s kitchen next door, and still seen with a separate ladies entrance where there was table seating. Other places had co-ed mixing, like McCoy’s bar (later named Gavin’s) on 2400 Lombard Street, which today is Rival Bros coffee, as well as Callahan’s at 2615 South Street, still in service and known back in the day for their weekend piano player and various singers. Like people today identify with their college sports team, men of the past identified with their bar, whom they represented in the summer softball league.

Another priest, Fr. Joseph Kirlin, would form a similar society, The League of the White Cross, a co-ed group of about 400 members, focusing on abstinence and entertainments. It is written of them: “Men gave high class minstrel entertainment and furnished vocal music, always keeping in the foreground the threefold pledge: personal total abstinence, promotion of abstinence among others, and discountenancing of the drinking customs of society.” Fr. Kirlin was also the primary author of our 1940 history of St. Patrick’s Church. By 1906, St. Patrick’s total membership in abstinence societies was 1530, the largest in the archdiocese. (Fr. Kirlin left to be appointed pastor of Precious Blood parish in 1907 and would become the long-time director of the Eucharistic League. The same year he completed his book Catholicity in Philadelphia. He was also the primary author of our 1940 history of St. Patrick’s Church.)

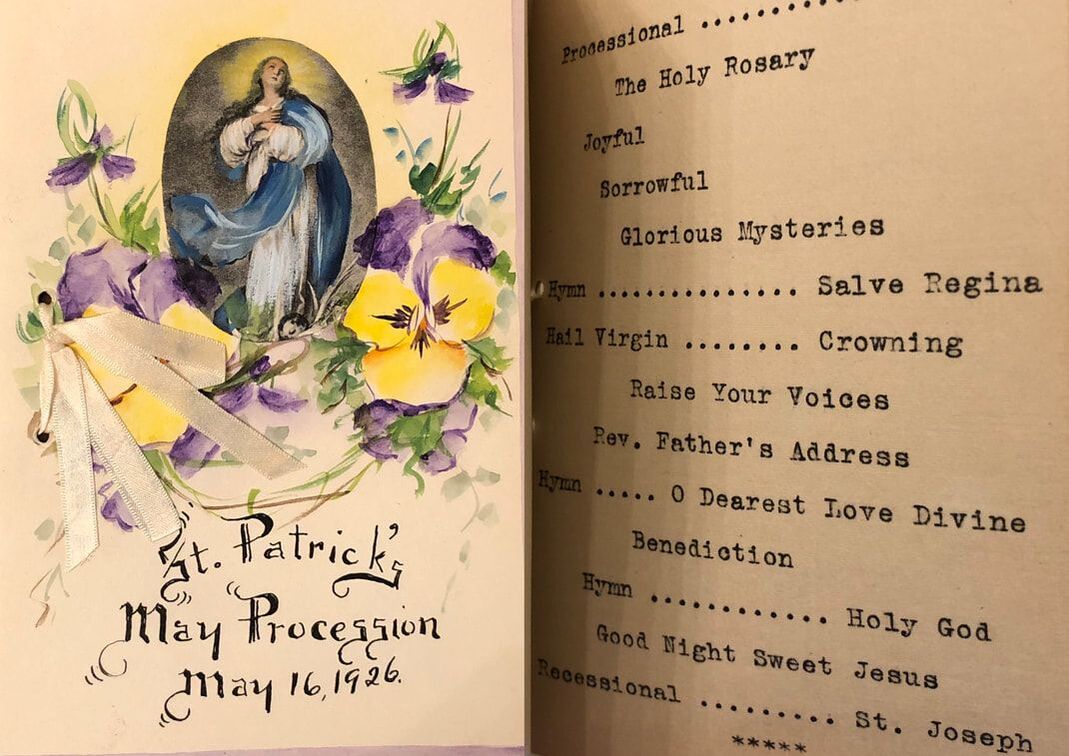

Other societies, of course, existed. In 1850, Fr. Devitt had adopted from the nearby Jesuits into his parish the Sodality of Blessed Virgin Mary. Besides their May celebrations with the crowning of Mary, they committed to weekly prayers, monthly communion, retreats, triduums, and (wait for it) Euchre tournaments. The card game, popular still in the Midwest, was likely invented in Philadelphia, when German immigrants confused the rules of their ancestral games after arrival in this country The Irish apparently adopted it as entertainment and fundraising all in one, and all in honor of the Mother of God.

In 1900, the society celebrated their Golden Jubilee, by then growing from an original 40 members to 1,200. Evening benediction was preached by Fr. William Stanton, S.J., who spoke on Mary as the most powerful means of leading men, and who lauded the people’s devotion, in his words, “50 years of singing the praises of her whom they love.” A crown made for the Mary statue was crafted from jewelry offerings by various women of the society, still used by the parish today at our May Crowning. (The family of its fashioner, Peter Schmidt, just visited the parish this past year asking to see the crown he took 3 painstaking months to complete.)

Further societies include the 1843 Society of Our Lady of Mercy, a women’s effort to serve the poor. By 1857, they transferred efforts to new St. Rose Society, going beyond fundraising and offering girls’ sewing classes in the parish hall to then donate the clothing to nearby families. The St. Rose statue in our lower chapel is from this society, and it was transferred along with many others from the old church to the new lower chapel. Men of the parish had long belonged to the Aid Society, which in 1858, became the St. Vincent de Paul Society. One creative effort was made by Patrick Spellissy in 1896 who successfully petitioned state legislators in Harrisburg to grant status to all society members as prison visitors. All these societies would offer generous help in later crises like the 1918 Spanish Flu and the 1929 Great Depression.

|

Since 1860, O’Hara’s Literary Society had hosted lectures and also staged many plays, from “Our Boys” to “Sweet Lavender” and “An American Citizen.” The Irish drama “Arrah na Pogue” by Dion Boucicault was considered their best play and staged 12 separate time, with the second most popular as Denman Thomas’ “The Old Homestead.” Shows typically ran 4-5 nights in the parish hall, and at times the players were invited to perform further shows at the Academy of Music or other city stages. Proceeds went to the Vincent de Paul Society, but likewise to the local Maternity Hospital for single mothers and the House of the Good Shepherd to offer safe haven to girls from brothels, a sobering reminder that past times had past problems. Beyond book and plays, the Literary Society also was famous for pool tournaments, dances, card games, concerts, and bowling.

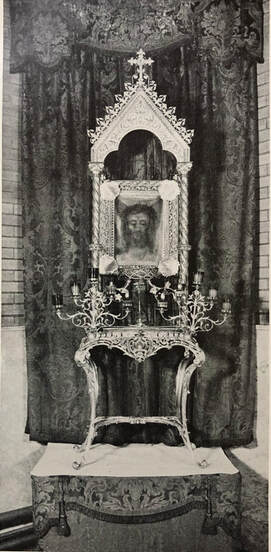

In 1889, the Society of the Holy Face was founded. 1040 members joined in the first year, and an image was enshrined in a side chapel, which parishioners today remember was still displayed during Good Friday not long ago. |

The short-lived Catholic Club of 1909 was known for their organized dances and wrestling bouts! They also had competitive track and and basketball teams, but by the 1930s they had expired. An Athletic Association also existed for a long time in the parish. 1912 saw the founding of the Holy Name Society, a movement among men to revere the name of Jesus and to cease all vices of profanity. They were assigned 6 associate priests from St. Patrick’s at one time to act as spiritual directors, but that doesn’t compare to the 10 priests assigned to the Marian Sodality!

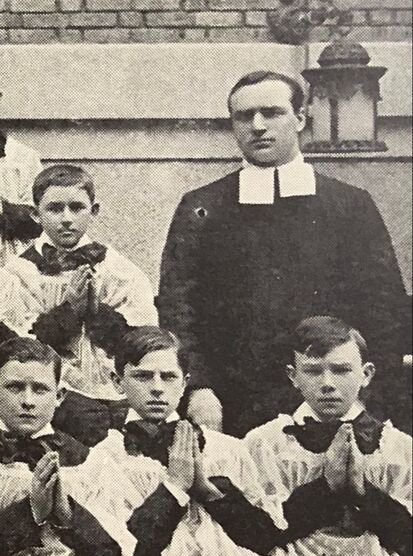

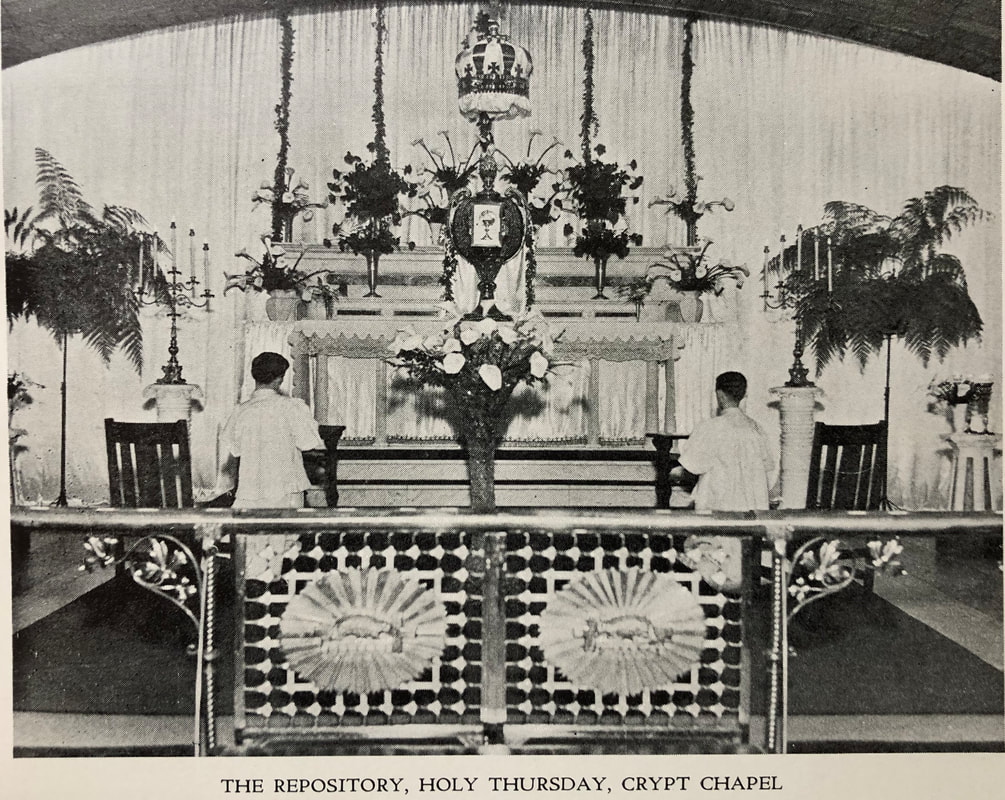

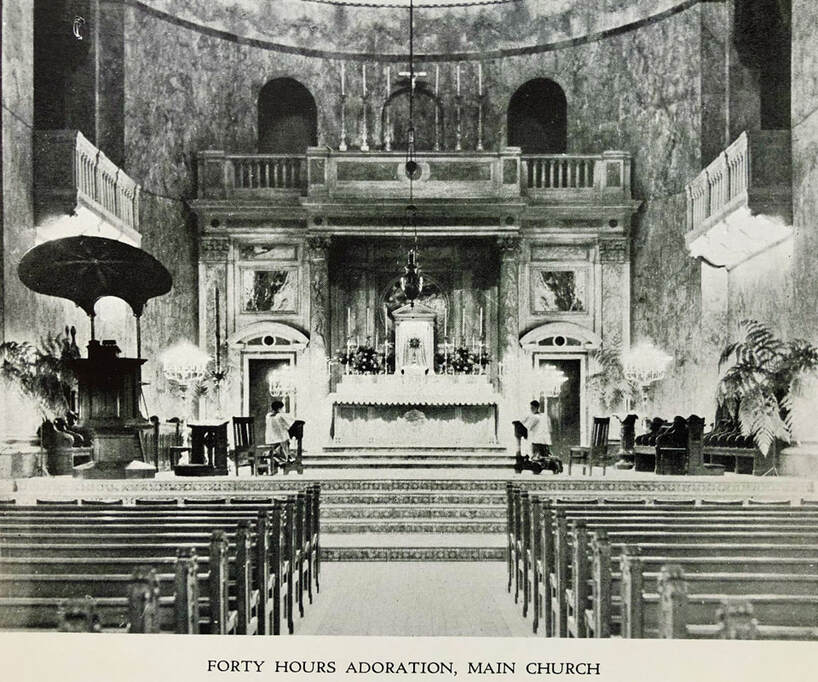

Other societies throughout the year include: The Ushers Association, The Convert League for non-Catholics seeking information about the faith, the Propagation of the Faith which found avenues of evangelization, and finally the Altar Boys’ Guild. Long-time parishioner Jimmy Stewart remembers the altar boy picnics which Fr. Joseph Fonash (a former Navy chaplain) would lead out to St. Charles in Overbrook, how the city boys had never seen cows before! “We altar boys were the guardians of the Blessed Sacrament. It was us they made stay up all night on Holy Thursday or Forty Hours' Devotion, on the kneelers, keeping watch. There was a rotation of boys, but you were always looking back, because a lot of them slept through their shifts. We would also have fights every Wednesday night at Fitler’s Square, all the altar boys.”

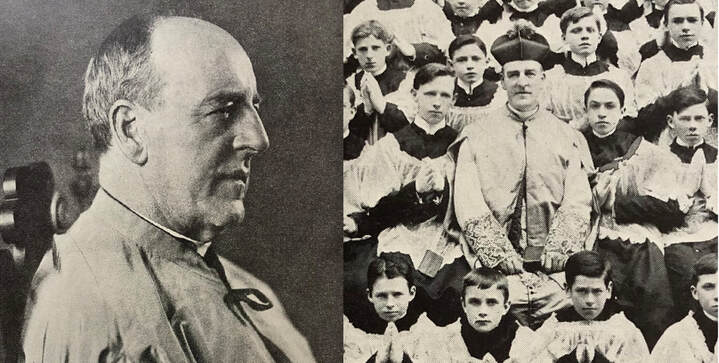

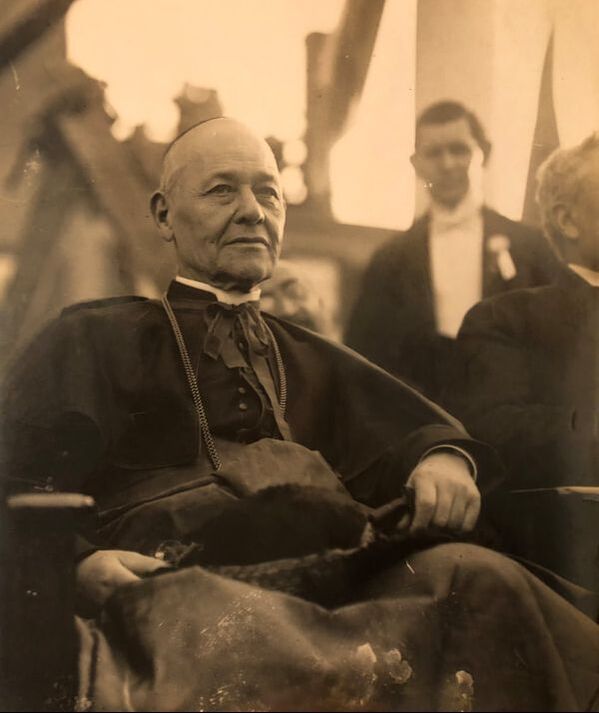

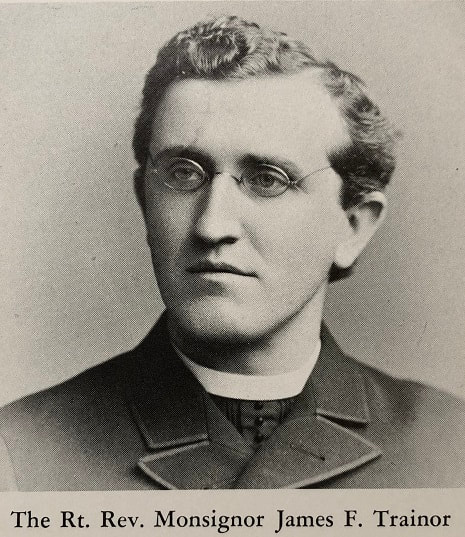

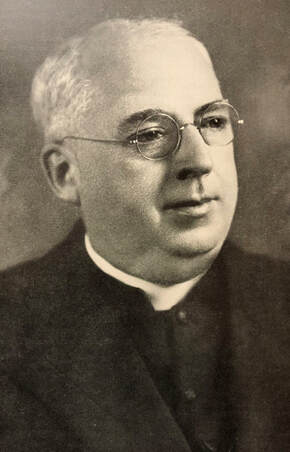

X. Our Longest Pastor

Who was Fr. William Kieran? In short, he was the longest reigning pastor St. Patrick’s has ever had. He is also one of the best. Named the fifth pastor on August 15, 1886, he would remain so until 1921, a total of 35 years, rivaled only later by Msgr. James Vallely’s 31 years which many present parishioners remember. (After the 3rd Council of Baltimore, certain pastors such as Kieran were named “irremovable rectors” who would stay on their assignment until death do them part.) Kieran would build our present church, further most of the societies listed above, and shepherd the parish through The Great War.

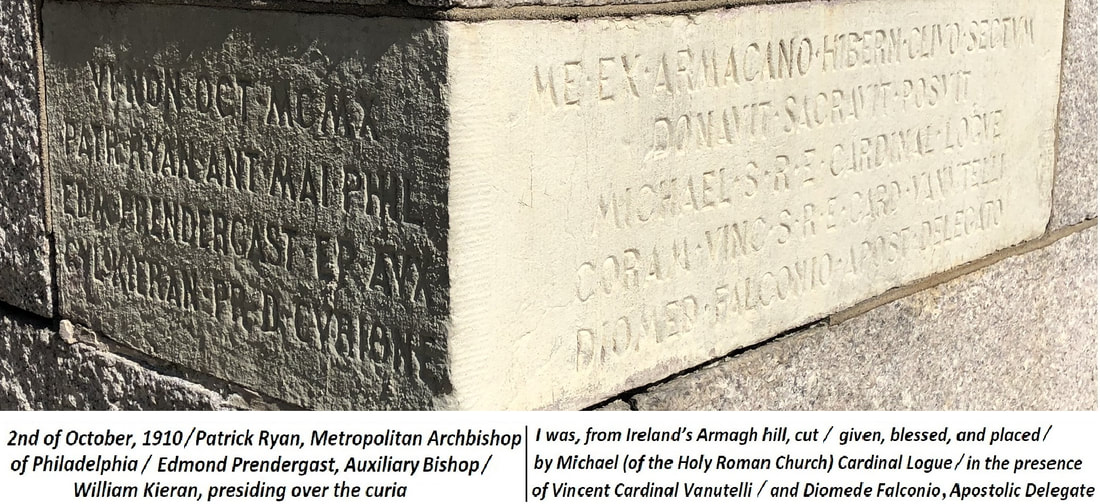

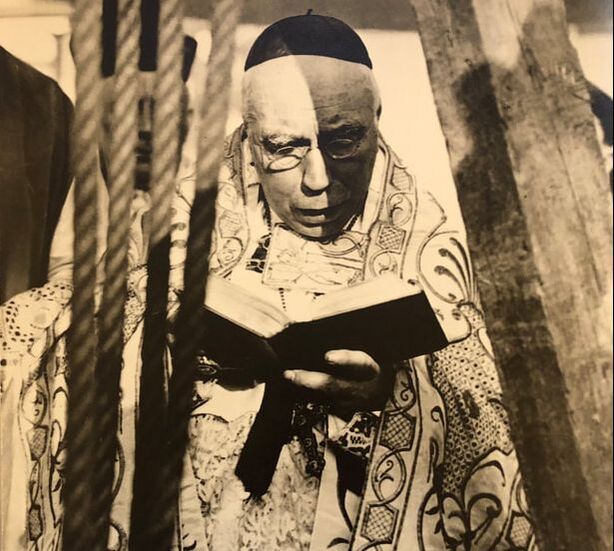

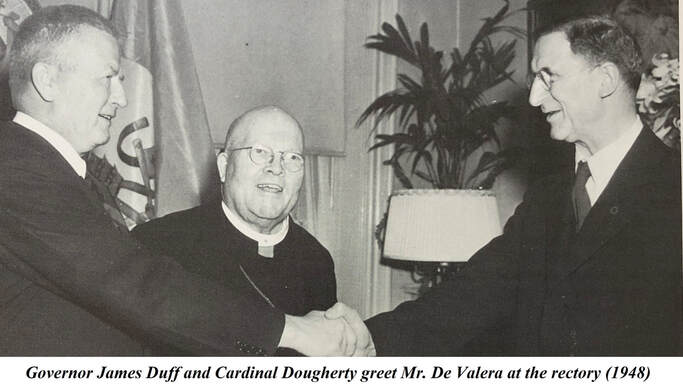

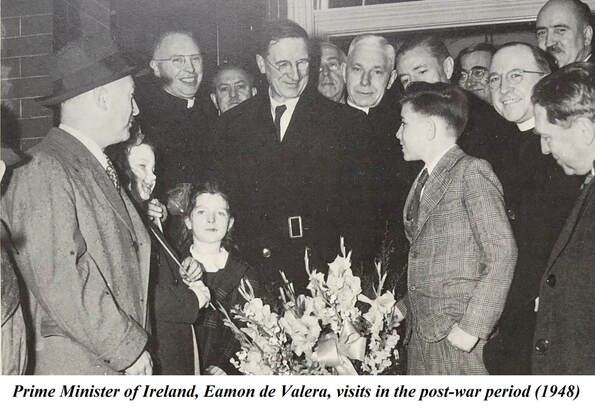

He was born in County Armagh, the see founded by St. Patrick himself as the center of the Church in Ireland and the site of the first cathedral Patrick built there in 445, a stone church on the Druim Saileach hill, where he also formed a monastic community. Michael Cardinal Logue, who would later visit our parish in 1910 for the laying of the new cornerstone, arguably the biggest event in our history, was to become the Catholic leader of Ireland as Archbishop of Armagh. To fast forward to the cornerstone ceremony is to realize that the pastor and the prelate both arrived overseas from the same county. Kieran only stayed there until he was 7 years of age, then immigrated to Philadelphia with his family, then spending his adolescence in residence with his mother at St. Anne’s rectory, as his brother, Thomas, was the pastor!

|

As a boy, Kieran was a sportsman, known to be natural and also “honest, fearless, and sincere.” With a further education, a contemporary described him as “almost painfully orthodox… yet taking him all in all, he was a Christian gentleman.” After a seminary education in Philadelphia, he was sent to the North American College in Rome, where he finished his studies, received ordination, and continued towards his doctorate. In 1869, Bishop Wood appointed him to assist his brother at St. Anne’s parish, then the cathedral soon after, until his 1873 seminary appointment as Master of Discipline and professor of sacramental theology. He would become Rector in 1882, now newly located in Overbrook, until his appointment as pastor of St. Patrick’s. Like O’Hara he would step from his position as seminary Rector into the care of our parish, except not retaining both jobs this time, as the seminary was better developed and could bid him farewell. He did begin to work in the diocesan court as “defender of the bond” in marriage tribunal cases. His time as pastor began by paying off small debts. Societies continued to develop. In 1891, the year before the church’s Golden Jubilee, the old baptismal font at which thousands had been received into the Church, was given to the new parish in Eddystone, St. Rose of Lima, and a marble one was erected in its place.

|

The jubilee of 1892. Altar boys headed the Mass procession, followed by elderly men along with James Carr, who had daily escorted the St. Joseph sisters from their 21st Street convent to the 6 a.m. Mass every morning. He did the same on this day. (The same one with the Christmas abstinence card, which he and his wife never went back on.) Also in the procession was Mother M. Evangelista, the first child baptized at the parish, then more than 50 visiting priests and other ministers. Music was realized by the grade school girls choir, Haydn’s 7th Mass, directed by Miss Nora Burke. She would be a long-time music director and organist, along with a certain Mr. William S. Thunder. (Most of the Solemn High Masses would be some setting of Haydn over the years.) Bishop O’Hara again visited to preside at the, but too sick to sermonize (he would die early the next year), Kieran himself offered a reflection on “the truth within these walls… shared in common even upon this earthen floor of our ancestors… all past parishioners now in the golden Jerusalem of heaven.” Archbishop Ryan was also in attendance and urged the faithful to “keep faith alive and green like all the decorations we see around us.” The florist bill, we can imagine, may have been steep that weekend.

1892 also marked the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the New World, which was celebrated throughout the diocese with Masses of Thanksgiving. Kieran’s own Silver Jubilee of 25 years a priest was also celebrated, with a Mass then a musical in the parish hall. And business carried on as usual. In the summer of 1898, Sunday announcements mention prayers for men of the parish, off fighting in Spanish-American War, but the record of names and numbers has not been preserved. Claire Keenan, a New Jersey resident, found through genealogical research that her relative Daniel O’Connell Harvey was a parishioner and was aboard the USS Maine when she exploded in Havana Harbor in 1898. He was the only Philadelphia resident to die in the event which sparked the war. He was also cousins with Fr. Henry McPake, a native vocation from St. Patrick's and priest at Annunciation parish.

|

In 1904, A new parish hall was built on 21st and Naudain Streets, with dining rooms, billiard rooms, a basketball court, bowling alley, and a theater. (Another nearby draw for many parishioners was the Knight of Columbus hall on 20th and Locust Streets, the red brick building still visible today, which hosted many meetings, banquets, and yearly parades.) St. Patrick’s new hall was the center of society activity listed above, which was truly its own sort of society. In those days before the automobile, the parish was one of the only options in the city for entertainment, from sports leagues to dances and movie nights. (Henry Ford would change the game with the first moving assembly line for cars beginning in 1913.) Some groups, such as the Literary Society, which staged many plays, operated out of their own row homes throughout the neighborhood.

|

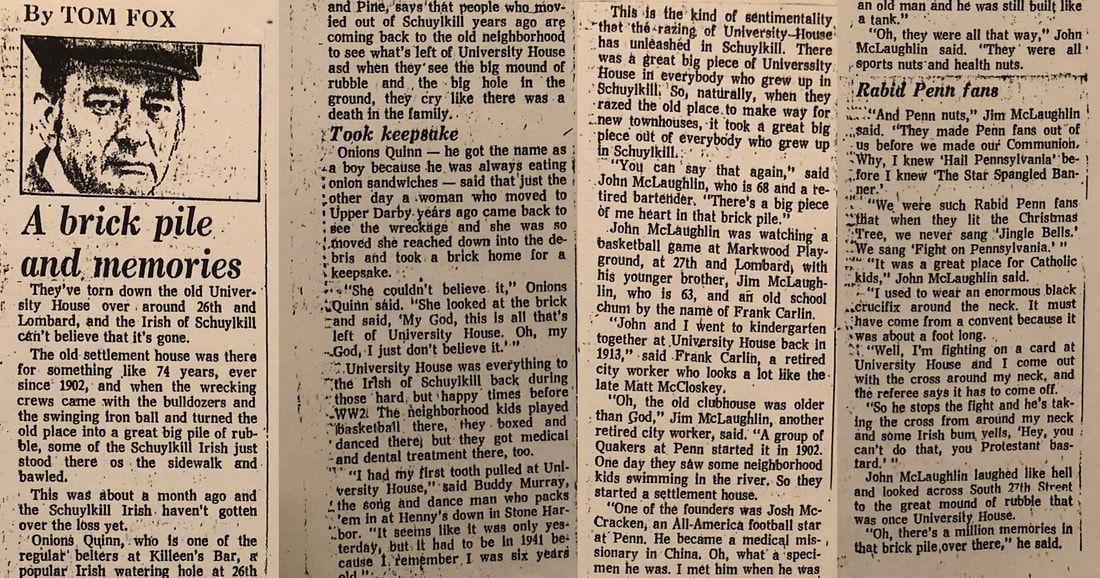

By the 1940s, extracurriculars had shifted away from parishes. Other options had developed in the area, and perhaps people felt more at ease recreating at more of a distance from their parish priests. The Avon movie theater on 23rd and South Streets had opened and drew many patrons. Parish hall activities were either duplicated or outdone by local community centers. For Schuylkill, this was the University House on 26th and Lombard Streets, founded in 1902 by a group of Quakers from the University of Pennsylvania. They were appalled to see poor Irish boys swimming in the river, filthy from industry, and so they opened a settlement house, which was a whole movement since the 1880s to bring services of the rich into poorer districts. Swimming in the river, however, was never discontinued. Boys and girls had separate days at the swimming pool on Taney Street, so on their off days the boys went to the South Street Bridge, which had two abandoned drawbridge houses with the doors always open and steps leading down to the bridge piers. They would dive off the piers or even out of the octagon windows in the stairwell, then swim upstream to the Walnut Street Bridge and back. Glenn Johnson reports: “99.9% of boys and girls from Schuylkill could swim. Taney pool went from 3 feet to 10 feet, so if you couldn’t swim they’d throw you in the deep end to learn real fast.” Still, the University House became a staple in the neighborhood. Among the founding group was the All-American athlete and Olympic medalist, Dr. Josiah McCracken, who later became a missionary to China.

All services were free: a theater for plays, a gymnasium for basketball, a kindergarten, a medical and dental clinic, a mechanic shop for cars, a social workers clinic. Tim McSorley says there were dances held every Friday for seniors and every Saturday for teenagers, the site of his first date with his wife, Cass. Sports leagues were also run from here, the main staple as a coach being Jim “Bloke” O’Connor, after whom the swimming pool on Taney Street is named today. Like other workers at the center, his was a volunteer position so he had a day job elsewhere. Unlike other workers at the center, he worked race track ticket windows, either in Bensalem or Cherry Hill. Perhaps one of the most amazing Inquirer articles featuring our neighborhood is the 1976 write-up on the demolition of University House. The local characters who comment on the scene here deserve a full hearing and not some cheap summary.